Twice-in-a-Lifetime Experiences

The Best Job Ever

By Jack Ewing

“The biggest caiman in the swamp always takes possession of the pool that surrounds the area where the cattle egrets nest,” I told the guests. “Whenever a clumsy egret chick falls in the water he grabs it.”

We had been observing a nesting site with hundreds of cattle egrets. It was nesting season and the small island of woody shrubs was full of egrets. It was located in a large open pool in a mangrove estuary. The egrets loved it because predators like raccoons, and coatis wouldn’t cross the water to get to the nests. I assumed they were afraid of the caimans.

I was trying to impress the guests, especially the woman. I had guided the couple on a different tour the previous day and saw lots of wildlife. Her husband loved the tour especially seeing wildlife, but nothing seemed to stir her emotion. After my declaration about the caiman eating the egrets I glanced over at them and the look on her face said it all. She just as well have told me, “Who do you think you’re trying to kid?”

Maybe she’s right, I thought, I’ve never actually seen a caiman eat an egret. I do know that the largest caimans hang out around the nesting site. Surely they eat any egret that falls in the water. Even though I haven’t seen it happen I’m sure it does. I wasn’t lying.

I decided to move on and turned to grab my spotting scope and tripod when a slight movement in the pool caught my attention. Right there in front of us was the largest caiman I had ever seen eating an egret. White feathers were sticking out of both sides of its mouth as it chewed. With a super human effort I managed to control my excitement. Pointing to the spectacle I commented as matter-of-factly as I could manage. “Oh look. There’s one right over there.” I quickly set the spotting scope on the reptile’s head, and both guests got to see it up close. After a few minutes the caiman finished its meal and sunk beneath the surface. We were ready to move on. Even after an amazing scene like we had just witnessed, I couldn’t detect the slightest trace of excitement on the lady’s face. After the tour she walked up to me, shook my hand, thanked me for a wonderful two days, and gave me a huge tip. I gave a sigh of relief. She really had enjoyed my efforts. If I guide for the next 100 years I’ll never witness another coincidence like today. That caiman grabbed the egret at the perfect moment.

I had been guiding for only three years when the above once-in-a-lifetime experience took place. When we first started offering rainforest hikes in 1987 I was the only guide. I loved every minute of it. The rainforest fascinated me, and guiding allowed me to go there every day and get paid for it. It was the best job ever. The big payoff was meeting so many wonderful people and sharing time with them exploring tropical nature. I soon discovered that people loved to hear stories, and telling a story about nature was the most effective way a guide could transfer knowledge to his/her clients. For example, let’s say we are walking through the forest and come to a large girthed, tall, straight tree with small thorns on the trunk. “This tree is called the sand box tree. It’s scientific name is Hura crepitans. We have a lot of them on Hacienda Barú. They aren’t very good for lumber.” The people will admire the tree take some photos, and we will move on through the rainforest. Five minutes later, they will have forgotten the name of the tree. If, on the other hand, I say, “Look at this size of this tree. Pioneers in this area used to make ocean going boats called ‘bongos’ out of them. The trunk is so thick that it can be hollowed out and made into a 20 meter boat. The sap is extremely poisonous and will blind you if it gets in your eyes. Even though the boat builders knew this and were very careful all of the ones I know eventually went blind just from working around them. Unscrupulous fishermen used to collect some of the sap and dump it in a stream. Then they would run down stream and gather all of the dead fish as they floated by. The seed pods are ring shaped. In the colonial days administrators would make a bottom for the ring and use it as a receptacle for sand which they could set on their desks. The fine sand was then sprinkled on documents written with quill pens to blot the fresh ink. For that reason they named it the ‘sandbox tree’”. This story will imprint itself on the guests’ mind and be remembered years later.

***

The vast majority of guests are sincerely interested in the rainforest and anxious to learn. They are a pleasure to guide. There are, however, a few exceptions. On occasion I have found myself with people who are difficult to guide and cause problems that lower the quality of the tour for other guests. Thinking back over my 16 years of guiding this hasn’t happened more than four or five times. The first serious problem happened when I had been guiding for six years. Everything started well. The guests, a young couple, were fascinated with the rainforest and asked lots of questions. When it was time to start back to the base they asked if we could continue onward, saying they would be happy to pay for the extra time. I looked at my watch, figured how long the return hike would take, and agreed to one more hour. We continued even deeper into the jungle. When the hour was up it was 4:30 in the afternoon, and the sky was clouding up. The lady was down on her knees following a trail of leaf-cutter ants through the forest.

“Okay everybody it’s time to start back,” I announced in an authoritative voice. “We’re going to have to hurry to make it out of here by dark.” The man walked right over to me ready to go. His wife continued following the ants and completely ignored me. I walked up to her and told her that we really needed to go. Again she ignored me. I stood there watching her for a moment and walked back to where the husband was standing. “This is serious Eric,” I told him. “If we don’t start now we won’t get out of here before dark, and I didn’t bring a flashlight.”

“Come Simone,” he shouted. “This is no time to play your silly little games. Forget about those f…king ants and let’s go. You wanna be here when it gets dark.” Again she ignored him. He turned to me, nodded toward the trail and said: “Come on! Let’s go! Just leave her here. When she gets this way there is nothing anybody can do. It’s all about getting her way, and not taking orders from anyone.”

I decided to give it one more try. I walked over to her again and, trying to keep my voice calm said, “I’ll find you some more ants to follow tomorrow. But we have to go now. Eric and I are leaving, and I strongly suggest that you go with us. I can assure you that you don’t want to be here when it gets dark.” She turned and looked at me, acknowledging my presence for the first time. “It’s your decision,” I said. “We’re going now.”

“Just leave her there,” shouted her husband. “The sky is getting darker.”

“Goodbye Simone.” I turned, walked over to her husband and started down the trail never looking back. I figured that if she didn’t follow I could return with flashlights and look for her. But I had to get Eric out of the forest while I could. Less than 50 meters down the trail we heard her hurried foot falls coming up behind us. Neither of us looked back. She sulked all the way home. We almost didn’t make it out. It was so dark that I had to feel my way along the last 200 meters of the trail with a walking stick.

***

In 1996 we were visited by a computer genius who had been one of the key players in getting the Internet going. His name was Phillip, and in addition to his computer skills he was one of the best photographers I have ever known. He was also a real character. I knew right away that it was going to be a pleasure to work with him. He had a big, heavy backpack full of cameras and lenses and lots of film. I commented to my wife that the contents of that bag was probably worth more than our house. Phillip was designing one of the very first travel web sites on the Internet, and wanted to include Hacienda Barú.

“I need lots of photos,” he announced. “But I’m talking about extraordinary photos of things that you don’t see on television every day. Don’t bother showing me ordinary stuff.”

“In that case we need to go to the canopy platform,” I replied confidently. “That’s our most extraordinary tour.” I went on to explain that we had built a platform 32 meters above the forest floor in the top of an enormous rainforest tree. We hoisted people up with an electric winch and later they rappelled down. It was mid-afternoon, and we decided to go right away.

We saw some monkeys, which Phillip photographed, on the hike up into the jungle where the tree was located. As platform guide I went up first and prepared to receive Phillip and his girlfriend Michele. Michele was also his camera bearer, though she weighed less than half as much as he. When a guest arrived at the platform she/he had to pass through a hole, which was big enough for a person or a big backpack but not both. Michele came next, followed by the camera bag, and Phillip came last. Once he reached the platform I tied him to a safety line, he stood up, looked around and started complaining. He wasn’t really complaining, he was just being difficult. It was part of his character.

“So why did you bring me up here Jack? What am I supposed to take photos of, all these tree tops?” And so on and so on.

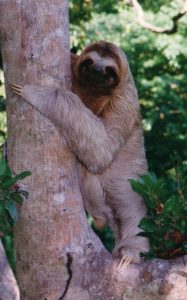

I was trying to think of a witty comeback when my eye caught a movement just behind Phillip’s head. A sloth was climbing down the trunk of the tree, no more than a meter away. “I don’t know Phillip. I have always thought the view from up here was pretty spectacular, but if that’s not good enough for you how about that three-toed sloth on the tree trunk right behind you. Is that the type of extraordinary thing you’d like to photograph?”

I will never forget the look on his face. He turned, grabbed the camera hanging from his neck, and started taking pictures, while at the same time barking orders to Michele. “Get me such and such a camera with such and such a lens. Here, take this one, it’s out of film. Reload it and fit such and such a lens to it. And so on and so on. In less than a minute the sloth had climbed down to a horizontal branch, stood on it, turned and faced Phillip, and, I swear, it smiled. It was the first and last time I have seen a sloth pose like that. By the time Phillip had gone through four rolls of film a couple of chestnut-mandibled toucans landed in the tree. He switched cameras and started taking photos of the toucans when four fiery-billed aracaris landed on the other side of the tree. After another lens change the photo session resumed. Within half an hour the toucans had left and the sloth was way out on a limb and a little too far to photograph. The frenzy of picture taking ground to a halt. We all sat down for a breather.

My thoughts returned to the tour when we saw the caiman eating the cattle egret. That sloth appeared at the perfect moment just like the caiman way back then. I’m really pretty lucky. I pondered. You’re only supposed to have one of these once-in-a-lifetime experiences, and now I’ve had two.