The Great Tinamou

The Great Tinamou (Tinamus major) known as the Gallina de Monte, or Jungle Chicken in Spanish, flies with great difficulty. According to some sources and based on fossil evidence, among the Costa Rica birds it is the most closely related to the true ratites which are flightless. These include ostriches, kiwis, moas, cassowaries, and emus. The only ratites in the new world are the rhea, of which I was fortunate to see several in the Pantanal National Park in Brazil. The ratites have a flat bony plate on the chest rather than a typical sternum or breastbone to which the flight muscles are attached in other birds. Their wings are small, but even if they were much larger, they still wouldn’t be able to fly because there would be no place to attach the flight muscles. Who knows, maybe they can surf on that flat chest.

The Great Tinamou (Tinamus major) known as the Gallina de Monte, or Jungle Chicken in Spanish, flies with great difficulty. According to some sources and based on fossil evidence, among the Costa Rica birds it is the most closely related to the true ratites which are flightless. These include ostriches, kiwis, moas, cassowaries, and emus. The only ratites in the new world are the rhea, of which I was fortunate to see several in the Pantanal National Park in Brazil. The ratites have a flat bony plate on the chest rather than a typical sternum or breastbone to which the flight muscles are attached in other birds. Their wings are small, but even if they were much larger, they still wouldn’t be able to fly because there would be no place to attach the flight muscles. Who knows, maybe they can surf on that flat chest.

The first tinamou that I experienced—I say “experienced” because I didn’t actually see it—was a blur of gray feathers bursting from the undergrowth with a loud whistle, zigzagging around trees, through the low-level jungle for a short distance, and alighting far enough away that it wasn’t visible. More than half of the tinamou’s muscle mass is dedicated to locomotion, but its heart is tiny. I imagine that is the reason they expend such a tremendous amount of energy using all that muscle to get off the ground but only fly a short distance before tuckering out.

The first tinamou that I experienced—I say “experienced” because I didn’t actually see it—was a blur of gray feathers bursting from the undergrowth with a loud whistle, zigzagging around trees, through the low-level jungle for a short distance, and alighting far enough away that it wasn’t visible. More than half of the tinamou’s muscle mass is dedicated to locomotion, but its heart is tiny. I imagine that is the reason they expend such a tremendous amount of energy using all that muscle to get off the ground but only fly a short distance before tuckering out.

Later I learned that a ghost-like whistle that sent shivers up and down my spine, and which I had frequently heard in the early evening was the call of the great tinamou. Giles and Skutch describe it perfectly in A Guide to the Birds of Costa Rica: “Deep, powerful, whistled notes, organlike in their deep swelling quality, among the most stirring sounds of tropical forest”.

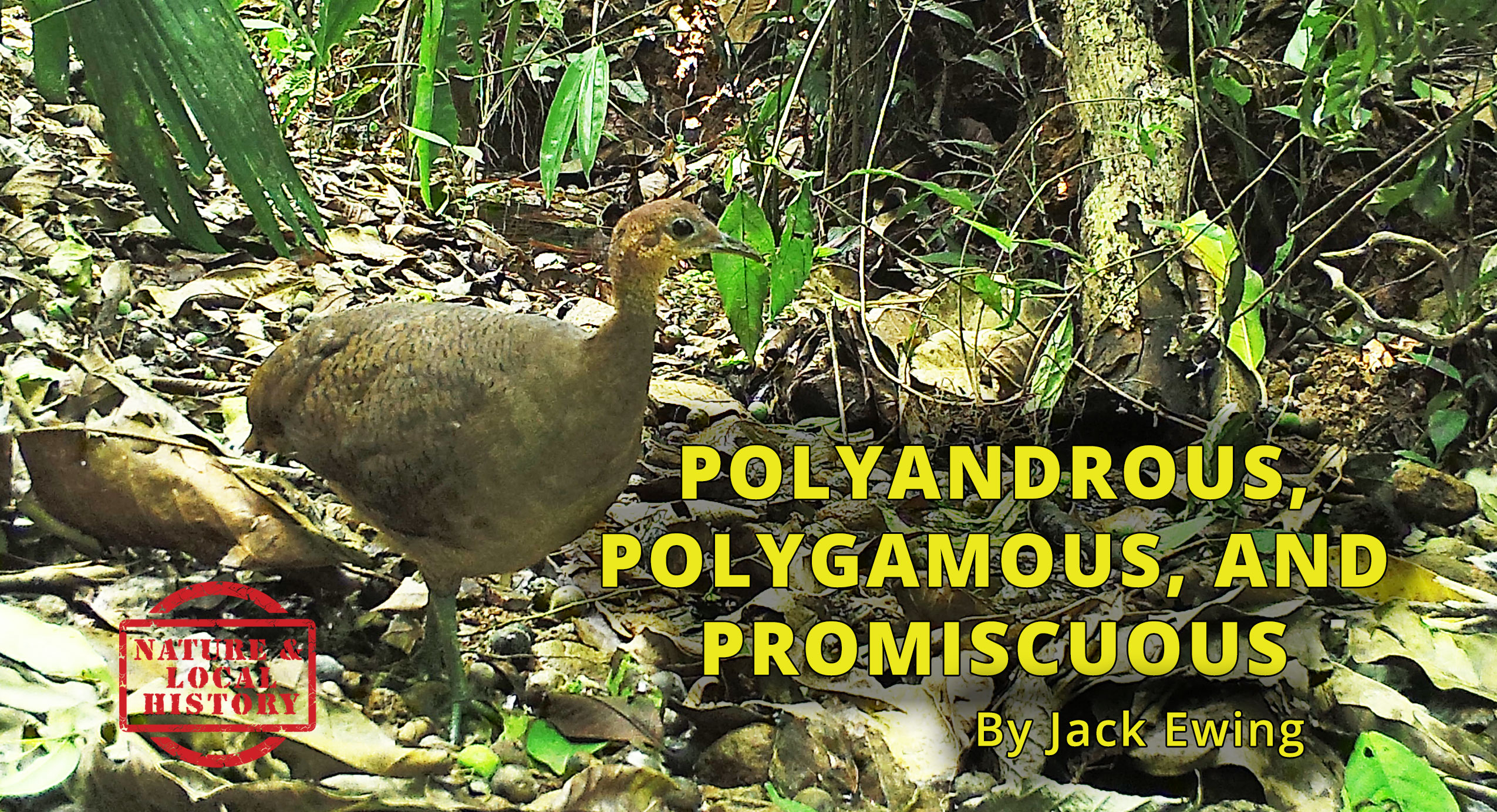

Poachers covet pacas and peccaries more than any other denizen of the rainforest, but they will kill a tinamou if the opportunity arises. They also need a lot of luck as hunters usually carry a 22-caliber carbine, and hitting a fleeing tinamou with anything less than a shotgun would be nearly impossible. Nevertheless, a shot from the carbine is loud enough to scare the birds and make them very wary of humans. For that reason, the roundish gray grouse-like birds became much tamer once we got the illegal hunting on Hacienda Barú under control. Today it isn’t unusual to see a great tinamou calmly walking down or across the trail in front of me acting as if I wasn’t even there. In fact, they are a great barometer for poaching. When they are being shot at, they are very skittish, and when not they quickly become tame.

Poachers covet pacas and peccaries more than any other denizen of the rainforest, but they will kill a tinamou if the opportunity arises. They also need a lot of luck as hunters usually carry a 22-caliber carbine, and hitting a fleeing tinamou with anything less than a shotgun would be nearly impossible. Nevertheless, a shot from the carbine is loud enough to scare the birds and make them very wary of humans. For that reason, the roundish gray grouse-like birds became much tamer once we got the illegal hunting on Hacienda Barú under control. Today it isn’t unusual to see a great tinamou calmly walking down or across the trail in front of me acting as if I wasn’t even there. In fact, they are a great barometer for poaching. When they are being shot at, they are very skittish, and when not they quickly become tame.

Sometimes great tinamous are described as polyandrous, meaning the female mates with multiple males and the males raise the chicks. In reality, their mating habits are a bit more complicated. The males do make the nest, incubate the eggs, and care for the young chicks. And the females do mate with more than one male and lay eggs in more than one nest. But the male may also mate with more than one female and the eggs he incubates may be from several females, some of which he never mated with. Additionally, the female may lay the eggs from one male in more than one nest. I guess you could say that the great tinamou is polyandrous, polygamous, and just plain promiscuous.

The nest is a shabby affair that the male scraps together with a smattering of leaves and sticks, often between a couple of buttress roots. The eggs are bright, colorful, and shiny. The two nests that I have seen on Hacienda Barú have both had sky-blue eggs. The bright colors are strange as the predation of the eggs would seemingly be less if they were camouflaged. One popular hypothesis is that the male will be attracted to the bright colors and enticed to sit on the eggs, cover, and incubate them. Though I doubt the color has anything to do with it, snakes frequently prey on tinamou eggs. The colorful eggs are so attractive that some people raise tinamous in captivity and market the pretty eggs on the internet.

The nest is a shabby affair that the male scraps together with a smattering of leaves and sticks, often between a couple of buttress roots. The eggs are bright, colorful, and shiny. The two nests that I have seen on Hacienda Barú have both had sky-blue eggs. The bright colors are strange as the predation of the eggs would seemingly be less if they were camouflaged. One popular hypothesis is that the male will be attracted to the bright colors and enticed to sit on the eggs, cover, and incubate them. Though I doubt the color has anything to do with it, snakes frequently prey on tinamou eggs. The colorful eggs are so attractive that some people raise tinamous in captivity and market the pretty eggs on the internet.

At first glance, the great tinamou may appear plain and uninteresting, but after delving into its natural history, we find it totally fascinating.

Jack Ewing was born and educated in Colorado. In 1970 he and his wife Diane moved to the jungles of Costa Rica where they raised two children, Natalie and Chris. A newfound fascination with the rainforest was responsible for his transformation from cattle rancher into environmentalist and naturalist. His many years of living in the rainforest have rendered a multitude of personal experiences, many of which are recounted in his published collection of essays, Monkeys are Made of Chocolate. His latest book is, Where Jaguars & Tapirs Once Roamed: Ever-evolving Costa Rica.