Milo Bekins Faries

by Carol Vlassoff

by Carol Vlassoff

(en Español)

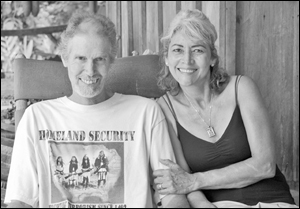

Milo Bekins Faries and his attractive wife, Tey, meet me in their forest home, four kilometres from Londres on the road to Cerro Nara. We sit on the veranda that encircles four sides of the house. True to the Bekins’ lifestyle, the house is built of cedro amargo and teak. Milo planted these trees on his own property years ago, with the idea of seeding their “house-to-be”. It is surrounded by forest gardens and a running water ditch moat that keeps their house amazingly insect free.

Milo, originally from Los Angeles, came to Manuel Antonio in 1974 “fresh out of college on a surfing expedition.” Having finished a marketing degree at San Diego State University, he and some friends traveled by local transportation from Mexico to Costa Rica, stopping to surf along the way. “Now surfers come and rent a car,” Milo smiles.

“I didn’t really know what I wanted to do in life before,” Bekins says. “You never know what your destiny is until you actually meet it. I didn’t know it until I came here.” He explains that he’d always been interested in the ecosystem, so he decided to stay and learn about natural ecosystems and sustainable organic methods of working the land.

He purchased a small house and two hectares of land for 50,000 colones (about $6,000 at the time) near the school in Manuel Antonio and set to work bettering his Spanish. “At the time there was no electricity or running water,” he recalls. “We were eleven expatriates living among the campesinos of Manuel Antonio.” With the help of his Tico neighbours he learned how to farm without the use of chemicals, practices he later perfected. For example, his composting methods have since attracted the attention of agricultural researchers in Costa Rica.

“After seven years of candles,” Bekins recalls, “we finally got electricity in Manuel Antonio.” But to him it was a mixed blessing. While he welcomed the electrification and running water, he also saw it as “the beginning of the end” of his quiet way of life Manuel Antonio. He says he did not want to go into the tourist business, so he knew he focused on his main interest, sustainable agriculture.

Around that time he met his wife, Maria Ester (“Tey”) Lezama Lopez which was a life-changing experience. Tey, a Costa Rican from Guanacaste, shared his interests in organic farming, having come from an agricultural family. Meeting her, he says, gave him a “more serious” direction, a direction that led him to Londres and homesteading.

Bekins recounts how he and Tey bought their first property by the bridge in Londres and started planting herbs and spices for the wholesale market. Although there were only a few spice and herbs growers in the country, they could not compete with the cheaper products coming to Costa Rica from countries such as India, Sri Lanka and Indonesia, where labour costs were about half those in Costa Rica.

Faced with this challenge, Milo put his training in marketing to the test. The hardest part of being a farmer, he explains, is marketing your crops. Planting, weeding and other processes are all easier. The solution he came up with was to eliminate the middle man and sell directly to consumer.

The strategy worked. He and Tey started what Milo calls “a Mom and Pop store” in Quepos, La Botanica, where Pali now stands.” In the 1980s, Milo says, many hotels and restaurants moved into the area, with a demand for fresh and freshly dried herbs and spices. “Businesses like the Plinio, the Mariposa, Si Como No and Gran Escape understood the difference that a real, freshly dried spice can make to their cooking.”

He and Tey also indirectly exported their products via the tourists who purchased their exotic merchandise. “We would grind it, package it and label it, and leave it to the tourists to export our product.” This, he smiles, was his way of “thinking globally, acting locally”.

Milo says that they ran La Botanica successfully for about 15 years. Many businesses came to rely on their products but this meant that every year they had to produce a large amount of spices – 25 kilos of vanilla and 250 kilos of black pepper, for example. “But nothing is forever,” he muses, “and we started growing older and wanting to do other things. In 2005 we sold the shop.” In this way, he says, they entered another phase in their lives and contributed to a “further phase in maturity of the ecosystem” through a new way of farming called “analog forestry”.

Over the years the Bekins had acquired the land where they now live and Milo worked both pieces of land. After selling the store, they sold their first homestead and moved to Finca Fila Marucha, the forest property they now call home. The finca was 94 hectares, of which 47 hectares were virgin, 35, secondary forest, and the remaining 12 had been cleared for cattle grazing. Bekins converted the farmland into forests which he designed to become analog forests. Analog forestry, he explains, aims to replicate the “architectonic structure” of the original forest as it was before man. “It is ‘analog’ because certain exotic crops are analogous in family types to what was here originally.”

Through studying the original forest Milo learned how to identify the “keystone species that make everything work.” He says they range from “strangling fig trees” to mammals such as bats, birds and animals. Only 3% of biodiversity of the rainforest are trees, he says. “All the life and complexities are working together to provide biodiversity – spheres of influence like the Olympic rings which are all intertwined”.

Bekins’ quest for sustainable biodiversity was inspired by a Sri Lankan, Dr. Ranil Senanayke, who first coined the term, “analog forestry”.

Before reading Senanayke’s works, he and Tey were trying to design a forest that was in tune with the environment, diversifying native and crop species, but they did not think of it in terms of imitating the structure of the original forest. Senanayke’s concept was different from simple reforestation. “Many want to reforest,” Bekins says, “but they end up doing industrial reforestation, planting with single crops like teak and not getting the rich biodiversity in their plantations.”

Milo says that analog forestry has many advantages: it provides a promising way of restoring forests, conserving the soil, sequestering carbon and enhancing the well-being of local communities. He points out that every tree has an ecological function, all providing the carbon essential for the fertility of the forest floor. Half of every piece of wood, he says, is pure carbon and another half of that is sequestered into the soil.

Bekins’eyes shine as he describes the complexities of the chemistry. “The components of the leaves on the ground provide the balance of the equilibrium and healthiness of that forest. We have the same diseases – fungi, bacteria, etc. – that plague the farmer, but in a forest they are under control and balanced out.” Analog forestry has another advantage, he says. It provides a farmer the option of keeping their land and making it productive, rather than being physically and socially displaced by selling out to foreign pressures.

“Ecotourism is one very good option for such farmers, and the government’s environmental payment services program provides financial incentives for environmental conservation.” Milo says that Costa Rica is the first country in the world to pay forest owners for conservation and carbon sequestering through its Payment for Environmental Services Program. He says that this policy will allow a farmer to keep and work the land, leaving most of it for conservation, while still allowing a few hectares for subsistence farming. Bekins serves on the Regional Environmental Council (CRACOPAC) of the Conservation Area of the Central Pacific to promote this program.

While Milo’s main focus is on converting his land into analog farming, he still produces and sells essential oils and to a limited extent, spices. I am treated to an intoxicating display of small bottles of citronella, lemongrass, ylang ylang, mint verbena, and many more aromatherapy oils.

Milo, who became a Costa Rican citizen 1987, is devoted to community service. For 15 years he has held many posts in Londres and Quepos and has helped secure grants for local projects in Londres from the Municipality of Quepos. These initiatives involved Londres community members both in their conceptualization and execution. He mentions six projects that were completed by community members through these grants, including building a chapel in the local cemetery, renovating the local health clinic and bringing in a medical doctor twice a week, and an activity centre. He also helped to bring garbage collection to the Londres community. Now the focus of Londres development is on conservation of the environment, a focus that is dear to Bekins’ heart.

Asked about the most rewarding experience in his professional life he talks about his leadership role in international conservation with the International Analog Forestry Network, of which he is currently Chairman. The Network consists of 27 non-governmental organizations worldwide, 23 of these in developing countries. Milo proudly explains that the Network has developed international standards for forest garden products, the only southern-based hemisphere certification standards in the world. “This is helping bridge the north-south divide,” he says. “The forest farmer can now provide a crop that is certified and exportable to other countries.”

Although it hasn’t always been easy, the Bekins have maintained a consistently positive attitude. “We try to live with no stress, no pressure, as you can see.” Milo sweeps out his arms to indicate the serene rain forest around us. Now their two children, Vivian and Esteban, are grown and married, and both live in Costa Rica,Vivian in San José and Esteban on the family farm, Milo says that he and Tey are now “buenos abuelitos” with two grandchildren, Milo Jr. and Alyssa. Happily for them, Alyssa lives just next door.