Hunting and Poaching

By Jack Ewing

At about 8 years of age I started going with my dad on Sunday mornings to his skeet club in Greeley, Colorado. I was too young to handle a gun, but loved watching him and his friends blow flying clay discs called “clay pigeons” out of the air with their shotguns. Even though I wasn’t shooting, my dad hammered firearm safety into my head on those Sunday morning outings.

My 12th birthday present was a 28 gauge shotgun. My first victims were doves, but I quickly advanced to ducks and geese. My dad loved hunting Canadian geese and took me with him two or three times each year. I bagged my first goose at 14. By the time we immigrated to Costa Rica in 1970 three large game trophies adorned the walls of our house, one set of deer antlers and two bearskin rugs. All of these were killed in Colorado and Wyoming, and all were legal licensed kills. My father and grandfather both taught me to abide by hunting laws and regulations, and, above all, to respect private property. “Always ask permission to hunt from the property owner,” they told me. “If he says ‘no’ don’t trespass.”

Costa Rica

In Costa Rica in the early 70s I once went hunting, unsuccessfully, for paca with some friends. Within a few short years I had become enchanted with the rainforest, and learned to look at nature and wild animals in a new and enlightened manner. Not only did I give up hunting myself but did everything in my power to stop people from hunting on Hacienda Barú. By the early 1980s I was starting to think of myself as an environmentalist. From that time forward Mother Nature and all of her natural checks and balances have never ceased to amaze me.

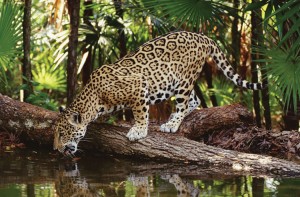

Prior to 2012 it was legal to hunt deer, doves, peccary, and pacas during limited and well defined seasons. In that year a modification to the Costa Rican Wildlife Law #7317 made all hunting and poaching in Costa Rica illegal. It also prohibited the capture and holding in captivity of birds and other animals. The only activity that has ever resembled trophy hunting in Costa Rica should more accurately be called “trophy poaching”. Unscrupulous hunting guides have charged foreign hunters upwards of $5000 to kill a jaguar in Corcovado National Park. The result has been plunging jaguar numbers there. To my knowledge none of these poachers were ever caught and punished. Prior to the passage of the new law the fines would have been insignificant. Now the maximum penalty for poaching is four months in prison and a $4000 fine, still much too low, in my opinion, for killing a jaguar.

I believe that the law prohibiting all kinds of hunting and poaching is ideal for Costa Rica. Populations of many of the species once hunted and poached are threatened or endangered and need to be protected. Costa Rica has set an example for the world by protecting 25% of its land in parks and nature reserves and by doubling its forest cover in the last 30 years. Today 52% of the national territory is covered with natural forests. The country is known for its leading role in ecotourism. Tiny Costa Rica has as many species of birds as all of the United States and Canada combined, and about 5% of the world’s biodiversity. The new law is another example of the country’s commitment to conserve nature. It is overwhelmingly popular with the general public. An environmental group acquired 177,000 signatures on a petition to the legislature requesting the passage of the law. It was passed quickly and unanimously. On a practical level the law provides the legal framework to deal with poachers on the rare occasions when they are caught. Lacking is funding for the enforcement of the law. In the meantime poaching is still rampant in much of the country. It is up to the individual land manager or owner to defend his own property, because little help can be expected from the wildlife department. Hopefully the government will look for a way to fund the enforcement of this popular law.

Colorado

Though I believe the law prohibiting all hunting is great for Costa Rica, it is not right for everywhere. An excellent example is the state of Colorado, where sound wildlife and fishery management have been in place for many years. Wild animals are seen as a renewable resource that can be harvested sustainably. Population numbers of large ungulates, like deer and elk, are estimated. Their natural food supply is also estimated and hunting licenses are issued accordingly. Colorado is home to the largest elk herd in the world, about 267,000 animals. This number is considered optimum for the amount of food available to them in their natural habitat. About 250,000 elk hunting licenses will be sold in 2015. This sounds like way too many, but wildlife managers know from past experience that less than one out of five hunters who buy licenses will actually kill an elk. This reduction in population will be offset by new births, and next fall the population will be about the same.

In Colorado it is legal to hunt deer, elk, pronghorn, bighorn sheep, mountain goats, moose, pumas, black bears, ducks, geese, turkeys, and pheasants. A license is required to hunt any of these species and there is a well-defined season and bag limit. Every year about 575,000 hunting licenses are sold in Colorado, 86,000 to non-residents. Non-resident licenses are much more expensive. For example an elk license for a resident costs $49 and a non-resident has to pay $600. In order to purchase any license you must show proof that you have taken a special course in hunter education and safety.

This year over $80 million worth of hunting licenses have been sold in Colorado and another $28 million in park entrance and camping fees. All of this revenue goes to the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Department to help cover their operating expenses. Among other things this revenue makes it possible for the department to vigorously enforce the law.

In addition to license fees if you figure in the value of all the goods and services sold to hunters and fishermen by Colorado businesses the value of the activity comes out to about $2.8 billion annually and 27,000 jobs created. Wildlife watching (ecotourism) brings in another $2.2 billion and generates 19,500 jobs. If any of you readers are interested in more facts and figures Google “Colorado Parks and Wildlife 2015 Fact Sheet”.

Needless to say, hunting and fishing is very important for the economy of the State of Colorado. I would imagine that any Colorado State Legislator who proposed a law similar to Costa Rica’s prohibiting all hunting would probably be strung up from the tallest tree on the capitol building’s front lawn.

Africa

The killing of the famed Cecil the Lion in Zimbabwe has focused lots of attention on trophy hunting in Africa. Some airlines have gone so far as to refuse to transport hunting trophies from animals killed by foreign hunters. The public outrage over the horrible killing of Cecil has been overwhelming, and rightly so. I won’t go into the gory details. I’m sure most of you have already heard them.

Nevertheless responsible trophy hunting is not necessarily bad for animal populations and local communities. We have seen the example of elk hunting in Colorado. There are many countries in Africa that permit trophy hunting in one form or another. Some countries have poorly managed programs that produce little income for local communities and animal numbers constantly decline. In addition to legal trophy hunting we have all heard of the toll that poaching is taking of African wildlife, especially elephant and rhinoceros. Several studies searching for solutions to the poaching problem have made some important discoveries. Most poachers are from local communities. They are poor and have families to support. They receive relatively little for the tusks and horns they poach compared to those above them in the chain of traffickers. Nevertheless it is a source of income that allows them and their families to live relatively well compared to their neighbors. In addition to poaching people often kill wild animals which damage their crops or kill their livestock. Rather than seeing wildlife as an asset they see it as a detriment.

On the other hand there are countries like Namibia which has a program that is producing positive results. In the mid-1990s Namibia initiated a system that guarantees local communities a say in the management of land and wildlife and a share in the monetary benefits derived from both ecotourism and trophy hunting. The program established local organizations called Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) conservancies. According to Jason G. Goldman, writing in Conservation Magazine, “The CBNRM finally allowed local communities to benefit directly, both socially and economically, from the wildlife with whom they coexisted.” The CBNRMs receive a percentage of the income from lodges and trophy hunting outfitters. The percentage is negotiated between the private business and the CBNRM, so there is some variation from one area to another. The amount paid by lodge owners averages about 10% of the lodge’s income, whereas hunting outfitters have to pay between 30% and 75% of their income to local conservancies. The percentage varies depending on the species being hunted. Additionally, lodges and outfitters are required to hire a certain number of community members. In all cases the trophy hunting brought in more money, but the ecotourism produced more jobs. The funds acquired by the CBNRM are used to pay expenses which include salaries for wildlife guards, park managers, administrators, vehicle maintenance, fuel, etc. The profit goes to community projects.

Robin Naidoo’s study determined that 74% of the CBNRMs studied, were operating in the black and 26% in the red. He did a simulation to find out what would happen if the revenue from either hunting or ecotourism were eliminated. The result was that if ecotourism were eliminated the percentage of profitable CBNRMs would drop to 59%, whereas if trophy hunting were eliminated only 16% would be able to pay their expenses. Without the CBNRMs a land area the size of Costa Rica with all of its wild animals would go without protection. These results are very encouraging. Namibia’s wildlife was in decline prior to the initiation of the program in 1997. Since then poaching has diminished, the killing of pest animals by local farmers has diminished and wildlife populations are stable or increasing.

Killing Animals

I speak to lots of groups of tourists from North America, and always mention Costa Rica’s no hunting law. Most visitors are very favorable to the law, but there are always a few in each group who tell stories of how wild animals have caused problems for them and their neighbors. This includes everything from deer invading and damaging gardens in residential areas to coyotes killing sheep. They always ask me if I would be against killing wild animals in such cases. “I wouldn’t do it myself,” I respond. “I no longer have a taste for that sort of thing. Costa Rica and the rainforest have changed me. Now I cringe every time one of our cats kills a gecko. But I certainly respect your right to hunt, as long as you don’t infringe on the law and don’t trespass on other people’s property.”