Wars, Politics, Roads, and Bridges

By Jack Ewing

In 1974 President Daniel Oduber began his four-year term as president of Costa Rica. Several months after the inauguration a small article appeared in the daily La Nación mentioning that the president and the minister of transport had stated that the planned coastal highway would be finished during his administration. The highway took a lot longer than four years to get to Dominical, and a lot more political promises were made and broken before its completion. The southern part of Costa Rica is one of the last areas of the country to develop. The roads and bridges that facilitated that development didn’t come easily, and they have a long and interesting history.

Around 100 years ago, when people from the Valley of the General — present day San Isidro – began exploring the coastal region around Dominical, they hacked a crude horse trail through the jungle to La Esperanza, San Josecito and finally arrived at the coast near present day Uvita. From there another trail was blazed to Dominical, mostly down the beach. Juan Bautista Ceciliano was ten-years-old the first time he rode to the coast with his brother Otoniel and their friend Nosario Segura. The year was 1915. The trail was almost nonexistent in places, and they often had to get off their horses and chop their way through the jungle with machetes. In the 1920s, long sailing vessels known as Bongos began transporting merchandise from Uvita, Dominicalito, and Quepos to Puntarenas. On the return trip they brought supplies that weren’t readily available in the zone; things like cloth, metal tools, salt and medicines. The existence of a means of transport for products such as coffee, sugar and tobacco to the market in the large port of Puntarenas, provided a big incentive to farmers from San Isidro to widen and improve the trails so that they would accommodate ox carts, which could carry more cargo than a pack horse. Getting products to market has always been a big incentive for building new roads and improving old ones.

Another incentive has been war. In times of war, roads become strategic even if they don’t happen to be in the war zone. A road far from the place where the fighting is taking place can be strategic because it is a supply route or because it is part of some contingency. During World War II the United States government was concerned about defending the Panama Canal in the eventuality that the Axis forces attempted to take it over. This would have been extremely difficult without a land route from the United States to the canal. At the time many regions in Central America lacked adequate roads. Completing the Pan-American Highway became a priority.

In 1940 a reasonably good road traversed the northern part of Costa Rica as far as the central plateau, and a narrow gauge railroad connected the Caribbean coast with the Capital. But the southern part of the country was not accessible by motorized vehicles. Something had to be done.

In 1941 the Charles E. Mills Construction Company landed a great deal of heavy equipment on the beach in present day Dominicalito. Remnants of the steel girders from the temporary pier they built for unloading the machinery were still visible up until about 1990. Once landed and organized, the company began building a road to San Isidro. The plan was to create a route from the coast to San Isidro, over which they could move more men and equipment. Once in San Isidro, the company organized itself into two construction teams. One started building a road toward Cartago by way of the Cerro de la Muerte, while another group started working toward Puerto Cortes, to the south. Another crew had already begun building a road from Cartago toward San Isidro and a third had landed machinery in Puerto Cortes, and split into two groups with one working toward San Isidro and the other toward Panama. By the time all of these crews had met their counterpart, the road was completed.

The main objective of the project was the completion of the Pan-American Highway. The road from Dominicalito to San Isidro was only a means of getting men and equipment from the coast to the Valley of the General. Once the highway was completed, the road to Dominical was was more or less forgotten by everyone but the people from Dominical and San Isidro who used it. They were the ones who repaired the road and kept it maintained, with only sporadic help from the government. Though the original road was very rudimentary and the passage was difficult, it nevertheless made possible the influx of a great many settlers into the zone. It marked the beginning of the massive deforestation of the region by the people who moved there to farm and raise cattle.

That first crude road was very steep in several places, the worst places being Las Farallas between Barú and Platanillo, and El Alto de San Juan between Tinamastes and La Palma. By the first time I came to Dominical in February of 1972, the Las Farallas route had already been altered to avoid the steep hill, but we still had to deal with the incline at El Alto de San Juan. On a later trip, the first time I brought my wife Diane to see Hacienda Barú, the back door of our Land Rover popped open going up that steep hill, and most of our supplies fell out in the dusty road. Over the next three years, the road was routed around that steep part.

On that first trip in 1972 there were only two bridges, one over the river at La Palma and another over the Guabo River at Barú. I’m not sure when the bridge in La Palma was built, but the bridge over the Guabo River, just above its junction with the Barú, was constructed in 1956 and 1957. Prior to that time there was a cable car – sort of a crude zip line — that allowed people to cross the river. Few other bridges were built until 1986, and until then most of the streams had to be forded. The only way to drive from Barú to Dominical was across a narrow suspension bridge over the Barú River. In the year 1986, the road from San Isidro was paved and the remaining bridges were built. The large bridge over the Barú River at Dominical was built the same year. Prior to that time we could cross the river at a point about 300 meters upstream from the present highway bridge. The crossing was known as “El Paso del Guanacaste” because numerous guanacaste trees adorned the banks on the Dominical side of the river. This crossing was possible only at low tide and only during the driest part of the year.

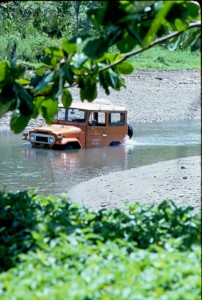

Diesel vehicles are better than gasoline for crossing rivers, mainly because they don’t have a distributor or spark plugs to get wet. But people with gasoline vehicles still needed to cross rivers and everybody had their own favorite technique for keeping the ignition system dry. Entering the stream on the run causes a big splash, and the spark plugs are almost certain to get wet. The first rule of crossing a river is to enter the water slowly and drive steadily to the other side, not too fast and not too slow. In high water, some people remove the fan belt so the fan won’t turn and splash water all over the engine. Another method is to put the vehicle in reverse and back through the water. Of course, it is always better to have four-wheel-drive, but not everybody did. Needless to say, getting stuck in the middle of a river or stream was a fairly common experience. People who owned farm tractors and lived near rivers made lots of extra money pulling stalled cars out of the water. Once in a while a vehicle would even get carried down stream.

In 1982 there was a very crude road going south to Uvita, and no bridges at all. That was the year the government began building the coastal highway from Dominical to Piñuela. It took many years to finish the project, but by the middle of the decade there was a reasonably good passage all the way to Puerto Cortes with bridges across most of the rivers. Going the other way, from Dominical to Quepos, the road had been passable for many years, but the only rivers with solid bridges were the Savegre and the Naranjo. The Hatillo Nuevo had a suspension bridge. People who lived near Dominical and needed to go to Quepos, could only do so in the dry season, as it was necessary to ford 13 rivers and streams. This situation also had its advantages, mainly that municipal officials had a hard time getting to Hatillo and Barú to collect taxes and business license fees.

Again, it was a military situation that worked in favor of roads in rural Costa Rica. The 1980s were times of turmoil in Central America with civil wars raging in El Salvador and Nicaragua and another on the verge of erupting in Panama. Apparently the United States government was concerned about an alternate route through Costa Rica and decided to promote the building of bridges on the coastal route of the Pan-American highway between the Savegre and Barú Rivers. In 1986 we got word that the US Army Corps of Engineers would be coming to build the bridges.

Though Costa Rica was not directly involved in any of the civil wars that plagued the rest of the isthmus, public opinion was polarized regarding who were the good guys and who were the bad guys. In El Salvador, the Soviet Union supported the rebels and the United States backed the government. In Nicaragua the situation was reversed. Costa Rica was officially neutral, but everyone in the country had an opinion. As you might imagine, the news that the US Army was coming to build bridges, precipitated a tremendous amount of commentary and gave rise to numerous rumors. Those on the political left claimed that the soldiers who were coming were drug addicted, disease ridden, insane Vietnam Veterans who would reek havoc in our communities, rape our women and corrupt our youth. It was even claimed that most of them had AIDS. Those on the other end of the political spectrum claimed that the engineers were the salvation of Costa Rica. There was very little opinion in between these two extremes.

Soon after the engineers arrived, it became apparent that there was nothing to worry about. Most of the men and women were much too young to have been in Vietnam. In addition to building bridges, they carried out community assistance programs. Medical teams visited each village and attended to a diversity of ailments and emergencies. A crew of engineers built much needed infrastructure for schools and churches. On Sundays, the soldiers played soccer with the local teams. And, of course, they really did build bridges.

During the construction a group of 30 engineers from the Costa Rican Ministry of Transport and Public Works (MOPT) worked with the US Army Corps of Engineers. The objective of their presence was to learn how to erect “Bailey Bridges” so they could do so in the future without the help of the US Army. They learned their job well, and are still erecting Bailey Bridges today whenever a bridge is needed in a hurry.

That first year soldiers camped out at a farm belonging to Don Carlos Rojas, located between La Guapil and Hatillo. The largest bridge built that year was over the Hatillo Viejo River. Five smaller bridges were erected over smaller streams. When the work was completed, Costa Rican President Luis Alberto Monge came to Hatillo for the inauguration of the bridge. It was a great honor for the small town to receive a visit from the national president.

The following year, 1987, the army engineers returned. They camped at the farm of Don Eliecer Castro, near Matapalo. That year they brought more men and more machinery and built the big bridges over the Hatillo Nuevo River and the Portalón River as well as five smaller bridges that hadn’t been completed the previous year. That was Oscar Arias’ first year in office on his first term. Don Oscar didn’t come for the inauguration, but sent a minor official in his place.

The torrential rains that came with Hurricane Caesar in 1996 sent a torrent of water down the Hatillo Nuevo River that took out the bridge. The engineers from MOPT, who had worked with the US Army Corps of Engineers, erected a new Bailey bridge in short order. In 2005 when torrential rains washed out the bridge over the Portalon River, it took a little longer, but within a year a new Bailey bridge was erected.

In the end, it wasn’t the administration of Daniel Oduber that finished the coastal highway, nor any of the administrations during the next 34 years. It was that of Oscar Arias who took office in 2006, and it didn’t take another war to get it done. The final leg of the highway between Quepos and Dominical was completed in 2010 to everyone’s delight, just in time of Oscar Arias to inaugurate it before leaving office.