The Story of Land and Sea in Costa Rica

Costa Rica is best known for its lush tropical environment and conservation ethic: monkeys, sloths, toucans, peccary, iguanas and agoutis all in a rainforest setting, in addition to whales, dolphins, and underwater wonders. This is what the visitor to Costa Rica will see and tell about. This is ecotourism at its best.

Those of us who live here love seeing the flora and fauna, both terrestrial and marine, but by virtue of being here all of the time we have the opportunity to see a deeper picture of our environment. We are able to see the environmental gains and losses, problems and solutions. Let’s have a closer look.

Use of the Land

Use of the Land

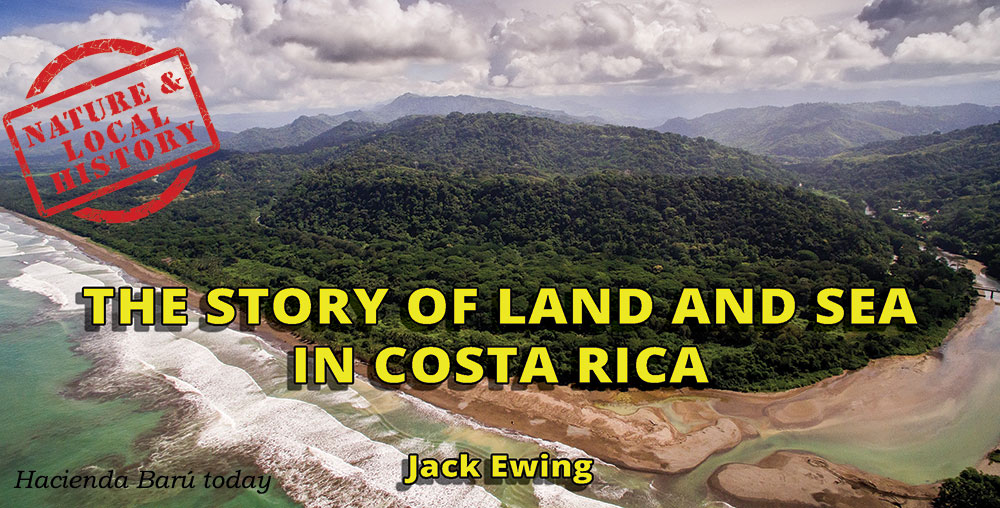

I used to be a cattleman and came to Costa Rica half a century ago to raise cattle. At that time Hacienda Barú, where I have lived and worked, was a 330 hectare (815 acre) cattle ranch where more than half the land had been deforested and planted to cattle pasture and rice. The neighboring properties were worse. I estimate that 70% of the land along the coast from the Savegre River south to the Sierpe Terraba mangroves had been deforested. Tapir, jaguar, puma, scarlet macaws, and three species of monkeys were locally extinct.

There was still some rainforest, mangrove, and other flora and fauna left, and I fell in love with it, and little by little became an environmentalist. I had the privilege of experiencing the transformation of Hacienda Barú and many other coastal properties into private forest reserves. Many cattle ranches along the coast were subdivided and parcels sold to new owners who only wanted a vacation home and had no interest in raising cattle. Instead they preferred to see toucans and monkeys around their houses. So they let the pastures get overgrown, and the jungle soon took over. Hacienda Barú became a National Wildlife Refuge. Today about 80% of the area is in primary or secondary forest or some other natural vegetation. The puma, scarlet macaw, and all four species of Costa Rica monkeys are seen on a regular basis, and jaguars and tapirs are sighted on rare occasions. The most important threat is illegal hunting which is practiced mostly by people who have regular jobs and hunt for sport in their spare time. There is no large scale bush meat trade.

The environmental ministry MINAE has done a good job with the meager funds that have been provided by the national legislature. They simply don’t have the resources they need to effectively enforce the laws.

With the impressive environmental gains over the past 40 years, the area has become an important tourism attraction, and a haven for bird watchers and nature lovers. Ecological tourism generates more income and more employment than any other economic activity.

The Marine Environment

The Marine Environment

The environmental health of the Pacific Ocean that borders the land described above, and the rivers that flow into it has faced some serious challenges. In the 1970s and early 80s we could see 50 pound snook swim through the mouth of the Barú River at high tide in search of smaller freshwater fish to eat, and it was easy to catch these hungry monsters. At least once a week we would hear of someone catching a 50 pound red snapper from the beach with a hand spool and line. I remember seeing people reach under rocks and pull out crayfish so large they could easily be mistaken for lobster by the unwary eye. Everybody who lived along the coast ate fresh seafood which was caught on a daily basis.

In the 1970s the inland areas of the country had no tradition of eating seafood, and more than once I was cautioned by friends from San Jose to eat fish or shrimp only at the very best restaurants. In those days the roads were so bad that it was difficult to transport perishable products from the coast to the major metropolitan centers, the trip was long, and fish sometimes arrived at the central market in San Jose in poor condition. Seafood got a bad reputation. As roads and transportation improved good fresh fish became available in the large cities on a daily basis. Today nearly everybody eats fish, and the major influx of tourism Costa Rica has experienced in the last 25 years has added even more to the demand. In addition to all of that there is a major export market for all kinds of seafood. With such an inflated demand, commercial fishing operations have developed, and everything from small local fishermen to fleets of trawlers are harvesting the fish faster than the marine environment can replace them. Those 50 pound snook and snapper are a thing of the past. The ones arriving at the markets today are much smaller. The fishermen are catching them before they have time to grow up.

Solutions

Solutions

The overburdened state of our oceans is a worldwide problem, and positive change will be much more difficult. The people who live and work in the coastal region have taken some important steps in turning the situation around locally. The creation of the Ballena Marine National Park 30 years ago has provided a viable alternative to fishing. Former fishermen have learned that conserving marine environments and taking visitors to see whales and dolphins, and go snorkeling and diving is a much more satisfying way to earn a much better living than the long, hard hours of fishing.

Ecotourism has done much to stimulate the conservation of our marine resources. We need more protected marine reserves and more well trained former fishermen to take visitors to see the attractions. We owe a lot to the thousands of visitors who come to our part of Costa Rica to see the flora and fauna, both terrestrial and marine. They have provided the incentive to turn the land area into one of the few places in the world where biodiversity is increasing and bring hope to the marine environment.