In Nature Table Manners Aren’t Part Of Eating

My sister and brother-in-law, live in northern Minnesota where they own and manage a nature reserve called Wolf Song. When they bought the land there weren’t any wolves. Now, after 40 years of rewilding, there are plenty. Recently, among other new species, they have been seeing lots of black bears. Not long ago Alan sent me a beautiful photo of a big, healthy, adult bear walking directly toward the trail camera. A couple of weeks later he sent me a video of a lame bear that probably had at least one broken leg. It could have been the same bear, but there is no way of knowing. They suspect it had been hit by a car on one of the local roads. A bear with a broken leg can’t catch any prey or wander very far to gather berries and other types of food. It has a minimal diet and will eventually starve.

One day I received a message from my sister saying they thought the bear had died because about a dozen vultures were circling near their house. I responded right away telling her that the vultures wouldn’t wait for the bear to die. As long as it was down and couldn’t harm them, they would start eating it bite by bite. First, they would pluck its eyes out and then go for the soft parts of its body. They didn’t care that it was still alive. It was food, and that’s all that counted. Alan tried to find the bear with the mission of shooting it and putting it out of its misery before the vultures got to work on it, but he couldn’t find it, and the next day the vultures were nowhere to be seen. No one knows what happened to the bear.

One day I received a message from my sister saying they thought the bear had died because about a dozen vultures were circling near their house. I responded right away telling her that the vultures wouldn’t wait for the bear to die. As long as it was down and couldn’t harm them, they would start eating it bite by bite. First, they would pluck its eyes out and then go for the soft parts of its body. They didn’t care that it was still alive. It was food, and that’s all that counted. Alan tried to find the bear with the mission of shooting it and putting it out of its misery before the vultures got to work on it, but he couldn’t find it, and the next day the vultures were nowhere to be seen. No one knows what happened to the bear.

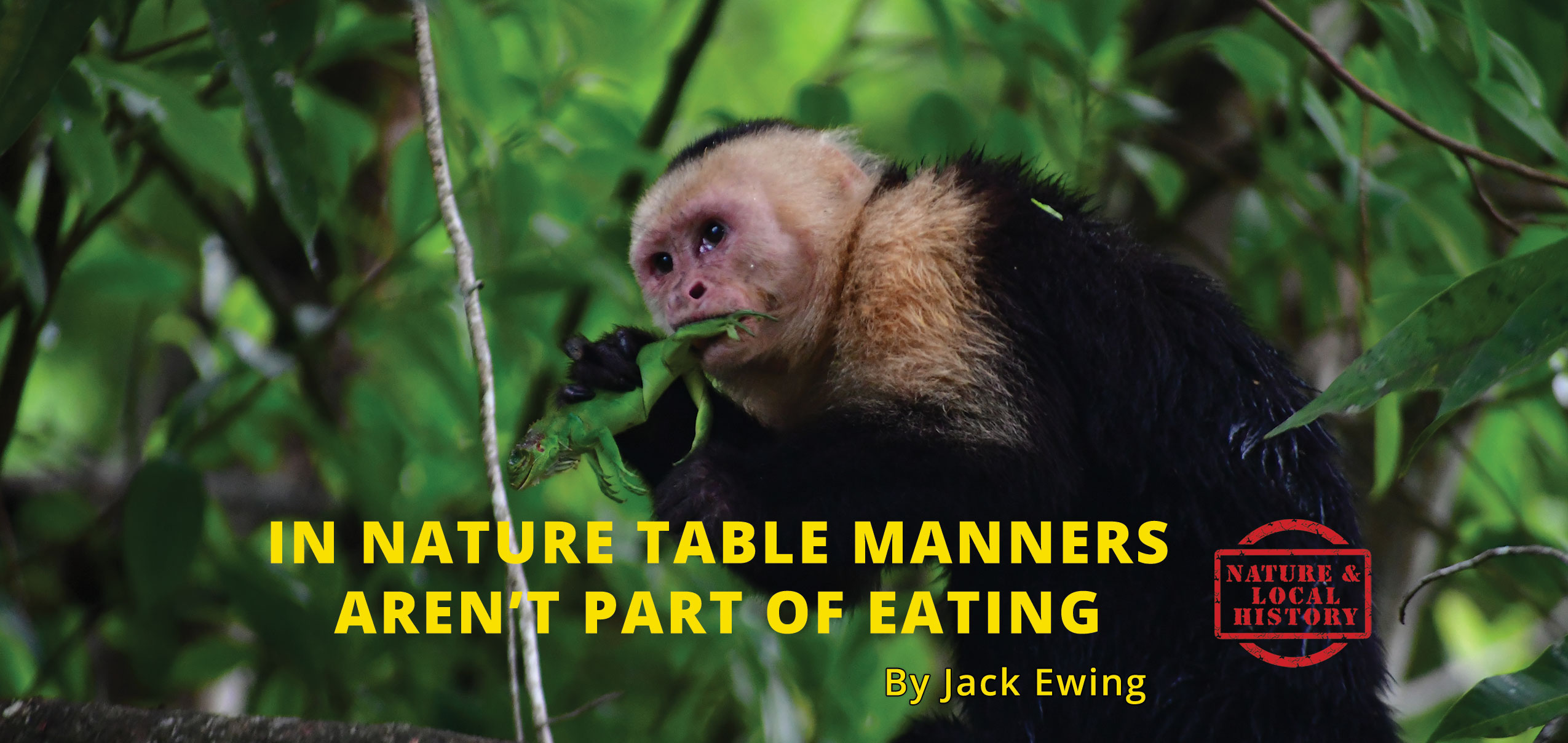

Vultures aren’t the only carnivores or omnivores that will start eating another animal that is dying but not yet dead. Some of the workers at Hacienda Barú once watched a group of white-fronted capuchin monkeys attack a big, fat, female, green iguana, rip her open with their claws, scoop the slimy mass of shell-less eggs out of her womb, and slurp them down as fast as possible, each monkey struggling to get a bigger share. When there were no more eggs to be had they tore her apart and ate her piece by piece even though she was twitching and struggling, obviously, still alive. Eventually, she died. Like the vultures, food is food. Eat it while you have it. Waiting around for it to die is not an option.

One of our guides captured a photo of a monkey eating a young iguana without bothering to kill it first. Spiny-tailed iguanas also catch and eat baby green iguanas, and, like the monkeys, they don’t wait around for the prey to die before commencing the feast. Bite, chew, and swallow is all there is to it. Kill is not part of the procedure.

Other species do things differently, they kill before they eat, sometimes. In my latest book Monkeys Are Made of Mangos, one chapter tells the story of a female puma that tortured a Yapok, (sometimes called a Water Opossum), for 30 minutes before it walked out of the field of view of the trail camera that was filming the loathsome event. The puma reminded me of a domestic cat “playing” with a mouse but stopping short of killing it. The yapok kept trying to return to a nearby stream and the puma would pick it up by the back of the neck, carry it a couple of meters from the water, bat it around with her huge paws, allow it to drag its battered body back to the stream and repeat the process. I don’t know if she ever killed or ate the yapok.

Other species do things differently, they kill before they eat, sometimes. In my latest book Monkeys Are Made of Mangos, one chapter tells the story of a female puma that tortured a Yapok, (sometimes called a Water Opossum), for 30 minutes before it walked out of the field of view of the trail camera that was filming the loathsome event. The puma reminded me of a domestic cat “playing” with a mouse but stopping short of killing it. The yapok kept trying to return to a nearby stream and the puma would pick it up by the back of the neck, carry it a couple of meters from the water, bat it around with her huge paws, allow it to drag its battered body back to the stream and repeat the process. I don’t know if she ever killed or ate the yapok.

Pumas are known to kill their prey with a bone-crunching bite to the back of the neck. I suspect it uses this procedure on prey animals that are too large to torment as it did with the yapok.

Of the Costa Rican felines, the puma is second only to the jaguar in size, but it will be wary of attacking a smaller animal that is capable of meting out a severe wound. Coatis are much smaller than pumas and are often preyed on by them. Nevertheless, if a puma attacks a coati and doesn’t surprise and kill it with one bite, the puma could receive a nasty wound before it finishes killing the coati. Coati bites and scratches and are often deep and susceptible to infection. Coatis have a knack for latching onto a patch of skin and ripping it off. A badly infected wound could bring death to the wounded animal. Wild animals can’t just run down to the emergency room for a shot of antibiotics.

Screwworms look like maggots, but there is a big difference. I remember my 5th grade science teacher had been a medic in the Second World War. One day he explained to us that at their field hospitals antibiotics were not available to treat infected wounds. As an alternative, they would allow blow flies to lay their eggs on the wound. The fly eggs hatched into short, fat, white, little worms called maggots. The maggots ate all of the dead flesh, but they didn’t touch the living tissue. Then the medics applied an antiseptic, such as tincture of iodine, which killed the maggots and prevented further infection.

Screwworms look like maggots, but there is a big difference. I remember my 5th grade science teacher had been a medic in the Second World War. One day he explained to us that at their field hospitals antibiotics were not available to treat infected wounds. As an alternative, they would allow blow flies to lay their eggs on the wound. The fly eggs hatched into short, fat, white, little worms called maggots. The maggots ate all of the dead flesh, but they didn’t touch the living tissue. Then the medics applied an antiseptic, such as tincture of iodine, which killed the maggots and prevented further infection.

As I mentioned, screwworms look like maggots. They also come from fly eggs, but a different species of flies. The big difference is that screwworms eat living flesh. If a cow, for example, cuts herself on a barbed wire fence; it is likely that a few screwworms will soon appear and eat away at the cut, causing it to get bigger and bigger with more and fatter screwworms. Cattlemen know that it is important to apply an antiparasitic liquid that will kill them. This must be done daily until the wound closes. Most use a product that kills the screwworms and, at the same time, promotes healing of the wound. If a wild animal has a wound that becomes infested with screwworms it has no way of eliminating them. The screwworms will keep eating until the animal dies. It will likely die from infection before the screwworms eat it to death. What a horrible way to die.

As I mentioned, screwworms look like maggots. They also come from fly eggs, but a different species of flies. The big difference is that screwworms eat living flesh. If a cow, for example, cuts herself on a barbed wire fence; it is likely that a few screwworms will soon appear and eat away at the cut, causing it to get bigger and bigger with more and fatter screwworms. Cattlemen know that it is important to apply an antiparasitic liquid that will kill them. This must be done daily until the wound closes. Most use a product that kills the screwworms and, at the same time, promotes healing of the wound. If a wild animal has a wound that becomes infested with screwworms it has no way of eliminating them. The screwworms will keep eating until the animal dies. It will likely die from infection before the screwworms eat it to death. What a horrible way to die.

And I thought Mother Nature was supposed to be nice. Nice is a human sentiment. Mother Nature doesn’t judge the difference between nice and nasty. She knows that food is essential, but table manners aren’t.

Jack Ewing was born and educated in Colorado. In 1970 he and his wife Diane moved to the jungles of Costa Rica where they raised two children, Natalie and Chris. A newfound fascination with the rainforest was responsible for his transformation from cattle rancher into environmentalist and naturalist. His many years of living in the rainforest have rendered a multitude of personal experiences, many of which are recounted in his published collections of essays, Monkeys are Made of Chocolate & Where Jaguars & Tapirs Once Roamed. His latest book is, Monkeys are Made of Mangos.