Improvisation

How do you make the transition from reading the notated music in front of you on a piece of paper to closing your eyes and just playing the music that somehow occurs to you? I’ve been asked this question a lot, especially from classically trained violinists who for some reason can’t make the jump from reading music to playing without written music and improvising. In my case, in order to get heard around my house you had to start improvising. Everyone in my family played music—usually written music, but when the whole family got together, unless you could ‘wing’ it, you wouldn’t be able to join in the fun. There were too many people crowding around the piano to see the music anyway. But I was lucky in having this background, because it was normal for us to play without written music and it wasn’t really a big deal. It was just what we did.

When I was in high school the local symphony people and music educators arranged for several Japanese violin students of the Suzuki Method of violin to perform and give workshops and such. As a sponsor of this cultural exchange, my family hosted a couple of the violinists who had learned by this method and they stayed at our house. The Suzuki Method, whose books and instruction methods I sometimes use in my teaching, basically teaches violin students to play by imitating and copying the recorded songs and instruction tapes that they provide. The theory is that if someone is exposed to well played music, they will play the same music in tune and correctly. They are trained to duplicate what they have heard. If they never hear music played out of tune, well then theoretically they’ll never play out of tune. The problem with this approach, to me, is that while they may play something precisely and competently, they are not getting inside of the music. They are not understanding why Bach wrote the way he did. They don’t necessarily learn to read music, so there is a huge musical resource that they don’t even know about, let alone take advantage of. A whole world of music that they are unaware of. We had a 16 year old Suzuki student stay with us, and she could play circles around me technically. She nailed super hard violin concertos and I was awed by her skill and concentration. But at the end of the night, when the rest of us were playing Happy Birthday for someone, she could not join in. A simple song that everyone, including her, knew—and she couldn’t play along.

My friend Michael played and studied violin as a child, and was a bit of a prodigy who learned and performed difficult pieces that required serious technical skills. At some point he abandoned his classical violin studies and over the years became a well-respected guitarist in New Orleans, playing in many different genres from rock and roll to cajun music to blues. He has had a wonderful career, is hugely respected by his peers and is totally comfortable with his guitar. A great player. One night, after a gig that we played together on, he confessed to me that he had started out as a violin player, and a hot shot violin player at that. So I handed him my violin and bow—it had probably been a couple of decades since he had held one in his hands. He carefully played a couple of scales, which were in tune and gave a glimpse of his former abilities. Then he tried out some of his old violin concertos that were still lodged back in his brain, and did pretty well with them. He was a bit clumsy and tentative, but it was obvious that he had at some point been very skilled. Then I started playing a fairly simple jazz tune—one that he had played on the guitar a million times—and he stopped. I mean he stopped like he had run into a brick wall. The melody that he knew was suddenly unavailable to him. He had never seen the written music for this simple piece, so somehow he just couldn’t access it on the violin. Kinda weird, huh? But this is a very common dilemma for classically trained players.

The first place to start is to understand keys. Every song is in a specific key, which is determined by how many flats or sharps are in the song. If there are no flats or sharps (they indicate a note being played a half step up or down from the actual note) then it is in the key of C. If a student is learning scales, they may not totally understand the keys, but they will read the music and play the correct note by bringing it up or down depending on whether a sharp or flat sign is next to the note. They may not realize that the notes they are reading determine the key, but they can play the music correctly by recognizing and playing the appropriate notes. People who play chordal instruments, like the guitar or piano, learn to play in keys—they may not learn which notes in the scale have flats or sharps, but they learn the chords that are appropriate to those keys. A guitar player can learn the chords that sound good and fit into the key of A, but they may not realize that they are playing 3 sharped notes (C, F and G) until they start learning single note melodies or scales. A key is just a simple way to re-state what is happening in the scale. And in written music, you don’t have to clutter up the page with sharp and flat signs since it is stated in the beginning of the piece. Once you understand keys, then you can understand and predict, somewhat, the progressions that will happen in the chordal structure of the song. You still with me? It’s just symbols—we learn how to interpret the symbols just like we learn how to read words.

The dictionary says that ‘improvisation is the creative activity of immediate musical composition, which combines performance with communication of emotions and instrumental technique as well as spontaneous response to other musicians.’ A performance without specific planning or preparation. Most of us think of improvisation as something that modern musicians do—jazz players especially, or blues, rock and bluegrass performers. But throughout the Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, Classical and Romantic periods, improvisation was a highly valued skill. Bach, Handel, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Liszt and many others were known for their improvisational skills. Many classical pieces contained sections for improvisation—they would be marked on the music by the cadenza sign as a place to play whatever the musician thought up. The preludes to some piano suites might state the chord progressions for the players to use, but not specific notes. A cadenza symbol might indicate where a vocalist can go crazy with their own vocal flourish, or a part to be played without a consistent rhythm—often allowing for a virtuosic display. A place to show off your skills and imagination.

In Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi classical music the raga is the tonal framework for composition and improvisation. The player learns the basic format and style of the music, then is free to embellish with their own ideas. An Irish fiddle player learns a tune, eventually teaches it to another fiddle player, and it evolves and is changed and becomes something new because someone started improvising and changed it. In the old days, the guys playing the piano to accompany silent movies had to interpret what was on the screen, matching and hopefully enhancing the style and pacing and intensity of what they were seeing for perhaps the first time. Those guys had to be quick on their feet (or hands) and have lots of imagination! Musical interpretation of art is a universal urge and a worthy endeavor—whether it be an attempt to explain dance or paintings or cinema or fashion or photography or literature or philosophy. All art is an effort to interpret life and our place on this planet, and to maybe explain or enhance our physical and spiritual journeys.

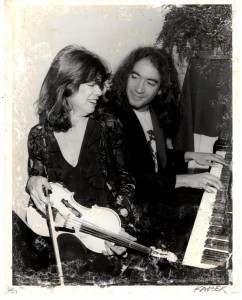

Manuel Obregon is a fabulous Costa Rican pianist, who studied classical music here and later at various prestigious European schools. He is probably the finest and most interesting musician I have ever had the honor to play with, and I learned much about improvising by listening to him and watching his process. He has absolutely no fear—sometimes he will prepare himself to play by completely emptying his mind of any musical references, whether melodic or rhythmic. He says he does not know what is going to happen until his hands actually touch the keyboard. Frankly that is a scary place for most of us musicians to go to. He has played for ballet and modern dancers, he has musically interpreted artwork. He is at home with Nicaraguan marimba players and Julliard music professors. Costa Rica’s biggest selling cd, ‘Simbiosis’, is Manuel improvising along with nature—I mean out in the jungle playing along with all the critters and birds. He has the skill, but more importantly he has achieved mental musical freedom and nothing inhibits him from musical exploration.

Improvising within a framework that we understand is a learned skill, but not a hugely intimidating thing. Improvising with other players—when everyone is on the same wave length and skill level and generosity of spirit and adventurous attitude—that is big fun and for many musicians that is their ultimate goal and happiest place. The appeal of ‘Jam’ bands is that they can play off of each other and be free to introduce new musical ideas, confident that their musical partners will pick up on what they are doing and join in with supportive and inspiring musical ideas of their own. For many of us musicians, those moments of combined improvisation are what we live for. Those times when the guitar player makes a musical statement that we all understand and latch on to and it all grows and expands and becomes something new and exciting and unique… It pretty much makes up for all the times of carrying heavy equipment late at night or eating at greasy on-the-road cafes or having to pay double for your drinks because the band is playing. No kidding, that has happened to me. I kept saying “but I’m in the band….”

As with most things, you learn by taking baby steps. If you play an instrument and want to learn how to improvise, then it’s probably a good idea to learn how things work in terms of keys, or rhythm, or some fundamentals of harmony. Then you throw in an extra note, or leave a space, or try playing in between the vocals, or you just close your eyes and play. The biggest hurdle is our own fear of the musical unknown, which is ridiculous really, as there are no wrong notes. Our choices of when to play the notes is what counts.

Ben Jammin’ and the HOWLERS play every Friday night at the beautiful and spacious Roca Verde, just south of Dominical, and every other Thursday night at the cool new beach bar in town, La Palma. We don’t always know what’s gonna happen, but we love that we can musically trust and truly play with each other and are free to improvise. Come check us out, as well as the other fine musicians around here, and please, always support live music and the venues who welcome and support us!

Master your instrument, master the music, and then forget all that bullshit and just play. Charlie Parker, jazz musician

To succeed, planning alone is insufficient. One must improvise as well. Isaac Asimov, writer

It was when I found out I could make mistakes that I knew I was on to something. Ornette Coleman, jazz saxophonist

Never play anything the same way twice. Louis Armstrong