How Our Towns and Villages Got Their Names

The origins of the names of places are sometimes obvious and sometimes obscure. The stories of how the places in the south central coastal region got their names are often interesting and tell us something about the area where we live.

Many places in Costa Rica were named by the church and our region is no exception. Examples of these are San Isidro, San Juan de Dios and San Josecito. A few villages already had local names when the church decided to give them the name of a saint. In these cases the inhabitants didn’t always embrace the new name.

Tinamastes is an example of a place where both the chruch name and the traditional name are used. The early settlers to the region cooked over an open fire, or in a fire box called a “fogón.” Much of the cooking was done either in a large pot or in a rounded cast iron platter called a “comal.” Rather that setting the pot or comal directly in the fire, three stones were placed in a triangular arrangement and the utensil was placed over the fire with the edges resting on the stones. These stones were called “tinamastes.” On a hill top near the present day village of Tinamastes, were three enormous boulders placed by nature in the same pattern as three tinamastes in a cooking fire. People began referring to the place as “Los Tinamastes,” and the name has remained to the present day. At a later date the church decided to change the name of the village to San Cristobal with limited success. Today both names are used by the residents of the town. Tinamastes is the seat of the District of Barú in the Cantón of Pérez Zeledón.

On the other hand the town of Matapalo, which was named after a parasitic vine is an example of a place where the church name never took hold. In tropical climates parasitic plants abound. One such plant is a vine with thick round leaves which completely covers the crowns of trees, eventually captures most of the sunlight and kills the tree. The vine is referred to locally as the “matapalo,” meaning “kill tree.” The first settler to the area, Juan Bautista Santa María Concepción, arrived by way of the beach, having walked northwest from the mouth of the Hatillo Nuevo River. Upon discovering a flat fertil area that appeared to be a promising site for agriculture, he decided to carve out a section of jungle and make his farm there. The most prominent feature seen from the beach was an enormous strangler fig tree with its crown completely covered with a “matapalo” vine, its tendrils drooping all the way to the ground. In describing how to get to his farm, Juan Bautista would tell people: “Walk down the beach until you get to the “matapalo.” Although the tree with the vine eventually perished, dried up and fell to the ground, the name was there to stay. At a later date the church tried to change the name of the community to “San Pablo,” but the members of the community kept calling the town Matapalo and, refused to use the new name. Matapalo is the seat of the District of Savegre in the Cantón of Aguirre.

I used to assume that a military general of the had once ruled San Isidro and the Valley of the General. If we delve into the history of the city we find that there never was a general or military presence of any kind, and the name probably came from the General River which had already been named when the town of San Isidro was founded. The source of the name of the river is not entirely clear, but some historians believe that since the river is the central waterway in the valley, and all other rivers and streams flow into it, the first adventurers to explore the region began calling it the General River, and hence, the Valley of the General. There are many places in Costa Rica called San Isidro, so the words “of the General” were added to the name to distinguish it. San Isidro is the seat of the Cantón of Pérez Zeledón.

Quepos, the seat of the Cantón of Aguirre, was named after the indigenous tribe that once inhabited the area. Puerto Cortés, originally called “El Pozo,” is the seat of the Cantón of Osa. The present name was given to it in the 1920s in honor of former President of Costa Rica, Leon Cortes.

Many places are named after plants. Though plants are not permanant fixtures, they often last long enough to become landmarks and end up lending their names to the place where they once stood. We have already mentioned Matapalo, but the Valley of the Guabo, Platanillo, Playa Guapil, Uvita and Dominical are others. Some of these have interesting stories behind them.

In Spanish a double-barreled shotgun is called a “guapil.” The word can apply to anything that has two cylinders side by side. At the entrance to what is today called Playa Guapil there once stood a coconut palm that was really two trees with the trunks stuck together like siamese twins or like a double-barreled shotgun. People started calling it “palma guapil” and later Playa Guapil. I once had a nursery of coconut palms. Out of about 1000 palm trees, three turned out with double trunks. Since the original double-trunked palm haa long since perished, I planted one of them on Playa Guapil, but within a week, someone dug it up and stole the tree. The same fate befell the other two as well.

The “viscoyol” is a sturdy cane-like plant with leaves similar those of a palm and a tough, straight stem lined with long, sharp spines. It is commonly found in humid soil throughout the coastal region. This plant produces bunches of small, round, purple fruits reminiscent of bunches of grapes. Grape in Spanish is “uva.” The word “uvita” is the diminutive form and means “little grape.” When people first began exploring the area around present day Uvita, the humid lowlands were covered with thick stands of viscoyol, and the people began to refer to the location as La Uvita. Hipolito Villegas, who was born in Uvita in 1909 says that it was called that when his father was born there in 1890. La Uvita is the seat of the District of Bahía-Ballena in the Canón of Osa.

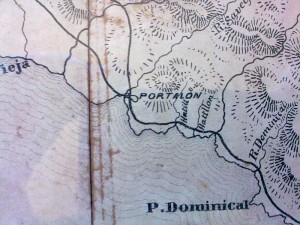

There is a well known local story of how Dominical got its name. In Costa Rica we have many different types of bananas including plantains, cuadrados, guineos and dominícos. In Spanish a field of bananas is called a “bananal;” of plantains, a “platanal;” of cudrados, a “cuadradal;” of guineos, a “guineal;” and of dominicos, a “dominical.” Before the appearance of roads, everyone walked down the beach to get from one place to another. In the lowlands near the beach of present day Dominicalito, one of the original pioneers of the area, Victor Sibaja — usually known by his nickname, “Chucuyo” — had a plantation of dominicos. When people walked down the beach and arrived at that point, they would say: “There is Chucuyo’s dominical.” For many years I believed this story, and it is certainly possible that Chucuyo did have a plantation of dominicos in present day Dominicalito. However I recently came across an 1868 map of Costa Rica that shows the stream that is today known as “Pozo Azul,” as the Dominical River. Also Punta Dominical is labled as “P. Dominical.” The name probably did come from the Dominico, but it existed long before Chucuyo was born. The place we know as Dominical today was formerly known as Barú or Boca Barú. Up until as late as 1958 the place known today as Dominicalito, was called Dominical. It is shown as such by a 1958 map of Costa Rica published by the Costa Rican Tourist Bureau (ICT.)

Another story about a place name that was put to rest by the appearance of the 1868 map is that of Portalón. According to old time residents of Poratlón, the first settler to establish a large farm along the river was Leitano Céspedes, who had the custom of building beautiful decorated archways and gates at the entrances to his properties. This type of gateway is called a “portal” in Spanish, and a very large one would be called a “portalón.” As more settlers moved into the area they referred to his farm by this most outstanding feature. However, Leitano Céspedes didn’t come to Portalón until the early 1900s, and there is a place called Portalón on the 1868 map. It is located near the estuary of the present day Savegre River. The Portalón River isn’t shown on the map. We may never know the real story behind the name.

Present day Barú is located about three kilometers upstream from the mouth of the Barú River, at the point where the Guabo River joins it. All of the other place names within the region have a local explanation, but Barú appears to be an imported name of indigenous origin. For over 2000 years people have migrated to this region from the south, especially from the area which is known today as the Chiriqui province of Panama, the home of a volcano named “Barú.” These people probably brought the name when they came to settle in this region. According to the linguistics department of the University of Costa Rica, the word “barú” comes from the indigenous language Guaymi. I once spoke with two native Guaymi speakers, neither of whom spoke more than a rudimentary market Spanish. I asked them about the meaning of the word “Barú.” Although the exact translation of the word is not clear, the meaning appears to be similar to that of the English words meaning “river basin” or “watershed.”

The village of Hatillo is situated between two rivers, the Hatillo Nuevo and the Hatillo Viejo. The derivation comes from the Spanish word “hato” meaning herd. Some of the pioneers of the area around present day Hatillo believe that a rancher from the Valle del Guabo, looking for new land on which to expand his herd, cleared an area between the two rivers where today we find the small town of Hatillo. Once the jungle was cut away, sunlight flooded into the area, and several species of grass began to grow. Once the natural pasture was well established, the cattleman drove a small herd of cattle from his main ranch about 20 kilometers away, and left them in the new pasture. He and his cowboys visited the site periodically to check on the small herd. In Spanish the diminutive of most nouns is produced by adding the letters “ito” or “illo” to the end of the noun. Therefore, if a regular herd is an “hato,” a small herd is an “hatillo.” The rancher and his workers referred to the small herd as “el hatillo.” Later when the coastal region became inhabited by settlers, the community that developed between the two rivers retained the name. If this story about the origin of the name is true, it had to have taken place prior to 1868, because both rivers are shown on the old map. The one which is today called the Hatillo Nuevo, was labled as the “Hatillo V.,” and the river we now call the Hatillo Viejo, was labled as the “Hatillon.”

The coastal village of Bahía was named after a large ranch called “Hacienda Bahía” that once existed near Uvita. In the 1950s the ranch was sold to the Alcoa Aluminum Company, which had the idea of mining bauxite. The mining venture never came to be, and the land was abandoned. In the mid 1960s, ITCO, the land and colonization institute, took title to the land, subdivided the ranch and distributed the parcels to landless peasants. The new settlement was called Bahía, after the ranch. It is located on the coast in front of the bay where Ballena Island is located, just to the southeast of Punta Uvita.

The name “Lagunas,” meaning “lakes” or “lagoons,” is ironic because the area has never had an abundance of water. Over the years the name has given rise to many humorous comments about a dry place called Lagunas. Nevertheless, about two kilometers above present day Barú, on the left side of the road is a small lake. Prior to the deforestation of the area, there were several lakes. Lakes are a rarity in Central America, and these small bodies of water were a notable landmark. The first pioneers to work the land in this area were Don Miguel Gómez and his sons. His oldest, Evangelista Gómez felled the rainforest and made his ranch in the area around the lakes. He and other settlers began referring to the area as “las lagunas,” which was later shortened to “Lagunas.”

I have always found the ways in which places acquire their names to be fascinating. As new information, such as old maps, come to be known, old ideas are often modified of discarded. Much of what is written here was told to me by pioneers to this area. The information comes from people’s memories and has never been written down. Therefore, it may not be entirely accurate. If any of you readers have information about the names of the places in this región, even ones not mentioned in this article, please let me know.