Clickity Clack Down the Track: The Atlantic Railroad in the Old Days

By Jack Ewing

They called it the “carro salón” or luxury car, though it was far from luxurious. I have also heard it called the “chair car” in English. Compared to the regular passenger cars, the carro salón had comfortable seats with plenty of leg room, a relatively nice restroom and a balcony on the back end. It had the distinction of being the last car on the train, right behind the caboose, so from the balcony there was a view on three sides. Beer and soft drinks were sold inside, and a short, fat lady with a checkered apron came through selling tortillas and empanadas. The wealthier people always rode on the carro salón, and everybody else went in the regular cars. All the trains had names. “El Pachuco” was the only train that had a carro salón. It traveled between Limón and San Jose daily, as did another train known as “El Pasajero.” “El Río Frio” traveled between Turrialba and Río Frio, but Guápiles was the most important station on the far end of that line.

The cattle ranch where I worked was located in a corner so it bordered the original, narrow gauge railroad line from Limón to Guápiles, la linea vieja, and the line from San Jose that joined it. The La Florida station and the La Francia station were both on the ranch, the former on the line from San Jose to Limón and the latter on the linea vieja.

The few adventurous tourists who visited Costa Rica in the 1970s and wanted to see Limón, always rode on the carro salón. I rode the train twice each week, once going out to the ranch at the beginning of the week and again when returning to my family in San Jose at the end. I met foreign tourists on the train about once a month.

One day in 1973, two couples from Chicago were on El Pachuco on their way to Limón. A couple of hours out of San Jose, several people were standing on the balcony talking. About the same time that the train slowed for a curve and a bridge, one of the men leaned against the boarding gate, which came unlatched and swung outward. The man fell from the train and landed on the hard gravel bed at the side of the tracks only moments before the car rattled across a 50 meter (110 foot) high bridge. The man’s wife screamed. Everybody stood staring over the railing off the back end of the car at the fallen man. The train clickity clacked on down the track, rocking slightly from side to side. His wife screamed louder. I ran to the next car forward, the caboose, and burst through the door to be met by the startled faces of the crew.

“Stop the train!” I yelled, “a man fell off.”

On either side of the caboose was an open door where a crew member stood looking out. “Nobody has fallen from the train,” declared one of them defensively. “We’ve been watching.”

“No, not there,” I blurted, desperately. “He fell off the balcony of the carro salon. You wouldn’t have seen him from the caboose.”

Not yet comprehending and still on the defensive, he again tried to explain. “We’ve been watching and….. Carro salón, did you say?” He pointed toward the end of the train.

“That’s right! Stop the train.”

The brake man pulled the emergency brake. The train slowed abruptly and screeched to a stop. He communicated with the engineer over the intercom, and El Pachuco began backing up, slowly. It took five minutes to cover the half a kilometer (0.31 miles) to where the shaken man was still sitting beside the tracks. Though a little battered and bruised, he didn’t seem badly hurt and, with a little help, stood up and boarded the train. He seemed to be okay in spite of his traumatic experience. Nevertheless, an ambulance met the train in Turrialba about half an hour later and took him and his wife to the hospital. At the end of the week, when I returned to San Jose, a crew member told me that the injured man had been released from the hospital and continued his journey to Limón the following day.

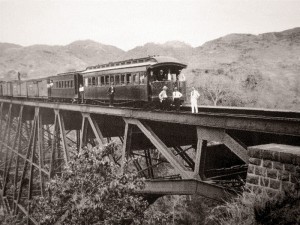

There was never a dull moment when traveling the trains. Landslides often blocked the tracks, especially along the steep sided banks of the Reventazon River, between Turrialba and Las Juntas, where the San Jose line met the linea vieja. Derailments, another cause of delay, were also common, but since the trains rarely traveled faster than 30 kph (17 mph,) this type of accident usually didn’t result in serious damage to either equipment or passengers.

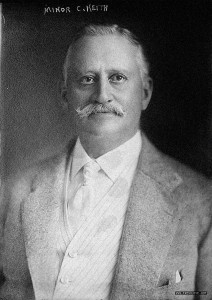

The Atlantic railroad was owned by the Northern Railway Company, which was founded by a British industrialist named Minor Keith, the man generally credited with accomplishing the gargantuan task of constructing Costa Rica’s first railroad. The project was begun in the 1880s and completed in 1891. Partially financed by United Fruit Company, the railroad made banana production feasible in the Atlantic zone.

Keith soon found that Costa Rican workers had little resistance to malaria and yellow fever and would not be able to provide the labor for building the railway, so he brought in black laborers from Jamaica. The Jamaicans were good workers and had a long history of resistance to tropical diseases. Had it not been for them, the Atlantic railway might never have been completed. Nevertheless they were offered little in appreciation for their role in making the railroad possible. Even Jamaicans born in Costa Rica were, for years, considered to be Jamaican citizens and were not granted the same rights as Costa Ricans. At first, blacks were allowed to travel no farther west than Peralta, a small town between Siquirres and Turrialba. Later they were allowed to go as far as Turrialba, then Cartago, and finally to San Jose and the rest of the country. This restriction on their travel was apparently not a law, but rather some sort of social restraint or perhaps a policy of the Northern Railway Company, the only source of transport from the Atlantic to the rest of the country. Eventually those of Jamaican descent, born in Costa Rica, were given citizenship.

The Chinese also played an important role in the building of the railway and the economy that sprouted up along its path. At end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, the immigration of Chinese to Costa Rica was prohibited by law. Laws, however, are often written for the common people and do not apply to the wealthy. In spite of the legal impediments Chinese were brought here to work as indentured servants in the households of well-to-do Costa Rican families. After a certain number of years of unpaid service, their debt was fulfilled, and their freedom granted. Most took the last names of their former masters and eventually acquired Costa Rican citizenship. I knew a Chinese man who lived in a place called El Cairo on the linea vieja. He and his wife were betrothed as children and came to Costa Rica from China at the age of ten or eleven. After gaining their freedom by working for fifteen years, they moved into the jungles of the Atlantic, along the railroad, and proceeded to make their fortune. Hard work and thriftiness over the years brought the family a respectable measure of success. When I knew them in the early 1970s they were in their 60s, owned several businesses and were considered wealthy. One of their daughters had gone to the University of Costa Rica where she met a Costa Rican boy whom she later married. Her marriage to a non Chinese, as I recall, was the greatest family crisis in many years.

As the sole form of transport, the railroad was the key factor for all production in the zone. In the tropical lowlands banana production was the motor that drove the economy, and in other areas it was cattle. The ranch where I worked was comprised of four farms that had been purchased separately and combined to make one 4000 hectare ranch. Part of the land had once been owned by Good Year Rubber Company and consisted mostly of rubber trees. The rubber trees were planted, and the community of La Francia built by Good Year during the Second World War. Part of my job in the early 1970s was to oversee the felling of rubber trees and the planting of cattle pasture.

Everything was coordinated from the main office in La Francia, which in addition to being our business office, functioned as a railroad station. As such we had a railroad telephone. Some of you older readers may remember back to the time when party lines were the norm and a private telephone line a luxury. The railroad telephones were the epitome of party lines. Ours had 52 parties, each with its own distinct ring. We could call the other 51 parties on our line, but it wasn’t possible to call outside of that line. Each telephone had a crank, and rather than dialing we turned the crank the specified number of rings, long and short. A full turn of the crank was a long and half a turn a short ring. Everybody on the line could hear the phone ring whenever someone made a call. Needless to say, our phone rang all day long. My ears never got attuned to the different rings, but the office help jumped whenever ours sounded: three long – two short – one long – one short. Most of the office help could identify all 52 rings. One time in an emergency, Mario, one of the office employees, called Limón and convinced the station manager to hold the receiver of the railroad phone up to the receiver of a regular phone and patch the call through to San Jose, but this service wasn’t available under normal circumstances.

Of all my experiences in the Atlantic, one remains highlighted in my memory. In October of 1973 two friends and I climbed onto a small flat car with railroad wheels and wooden seats. For several hours we were pulled by a mule, trotting along between the rails of an abandoned spur. Eventually the driver brought us to a stop at a canal whose lazy current emptied into the Reventazon River. My friends and I loaded our supplies on a small motor boat. The owner of the mule car, unhooked the mule, led it around to the other end of the car and pulled it all the way back to El Cairo. That night we slept in a couple of rooms on the second story of a pulpería (general store) located at the junction of the Reventazon and Parismina rivers, a place called Boca Parismina. The owner was Chinese. The following day we took the boat all the way to Tortuguero. The only business in the village was a small general store that was also a very informal restaurant. We had white-lipped peccary steaks for lunch. The area was known for great tarpon fishing, but we didn’t have much luck. It’s probably best that we didn’t hook a tarpon, as our fishing equipment wasn’t heavy duty enough for those big fighting fish. That night we returned to Boca Parismina, where we had slept the previous night.

The following morning, a Saturday, we rode our small boat to Limón where the driver left us and returned to his home. Before boarding the train to the south, my two companions and I passed by the home of the Panamanian consulate. We planned on crossing the border and wanted to make sure our papers would allow us to do so. The consulate gave us a letter of permission, which we paid for with a bottle of guaro (sugar cane liquor.) Our destination for the night was Cahuita, but the train went only as far as the town of Penhurst on the banks of the Estrella River, then continued inland to another town called Pandora and the banana plantations of the Estrella valley. We detrained at Penhurst. It began to rain as we were ferried across the river in a dugout canoe which the handler powered by pushing off the bottom with a pole. A truck was waiting on the other side. I remember the driver walking down to the river bank and brushing his teeth in the muddy water. We climbed into the back end of the truck for the wet 30 minute ride into Cahuita. The bus was having mechanical difficulties that day, and the truck was its substitute.

After a dinner of rice and beans, cooked in coconut oil, we slept in the only hotel in town. In reality it was about the same as our rooms in the pulpería where we had slept the previous two nights. The next morning the bus was working again, and we traveled around the country side until we reached the town of Home Creek, located right on the Panamanian border. The bus broke down again. It appeared that there was little hope of getting it fixed, so we abandoned our plan to visit Panama and hired a jeep to take us to Puerto Viejo. After that we returned to Cahuita where we spent the afternoon laying around on the beach.

The following day, the same truck that had picked us up two days earlier took us back to the Estrella River, where we rode the same poled dugout canoe across the river and boarded the same train at Penhurst. With a couple of hours to kill in Limón, I got a shave with a hot wet towel and a strait razor. About 3:00 p.m. we boarded our train in Limón and disembarked in La Francia a couple of hours later.

I remember meeting the Cahuita school teacher while waiting for the train at Penhurst. He was recently arrived from Jamaica and spoke excellent and very proper English, but not a word of Spanish. Most of the local people spoke a dialect called Patois, which appeared to be a mixture of English, Spanish and French. I could pick up a few English and Spanish words, but couldn’t understand the conversations. Almost everybody spoke English and the younger people spoke excellent Spanish.

Due to the influence of the English language on the Caribbean, many of the Spanish speaking people used words that were adapted from English. For example, a creek, which is usually called a quebrada in Spanish was called a “creekay” on the farm where I worked. The brake man on a train on the Pacific railroad is called a frenero which comes from the Spanish word for brake, freno. However, on the Atlantic Railroad the brake man is called the brakero.

At that time I owned a fat, loose-skinned, sad-eyed Basset Hound called “Pierre” that I really wanted to take to La Francia. However, the railroad had a regulation against taking pets on the train, supposedly because of the danger of bites and rabies. My friend and fellow worker, Harry, suggested that I drive him to Siquirres by road (jeep trail.) “We’ll figure out a way to get him on the train from there to La Francia,” he said with a wink.

My wife Diane, seven-year-old daughter Natalie, two-year-old son Chris, Pierre and I drove to Siquirres. We parked the jeep next to a gas station where people who had gone on the train left their cars. We walked Pierre over to the train station on a leash. He was the center of attention. One boy, looking at the folds of skin on his face, asked “Does that dog have eyes?” Somebody else remarked that we had better hold onto him tight or he would end up in the chop suey at some Chinese restaurant.

Harry and a bunch of his friends met us there. We boarded the train in a mob and shoved Pierre under a seat. During the short ride it was easy to keep him hidden with human bodies. When the conductor came by to collect the fares, everyone laughed and joked to keep him distracted. The conductor spotted Pierre as I was leading him off the train. “Hey, what’s that dog doing here?” He blurted. “You can’t bring a dog on the train.” I stepped from the train over to the boarding ramp, Pierre made the short leap with ease, glad to be out from under the seat and into the fresh air.

Harry turned to the conductor and smiled. “Don’t worry, we paid for his passage.” He stepped off the train as it began to pull away. The conductor threw up his hands in defeat.