A Snake in the Attic But No Bats – A Grand old House

By Jack Ewing

Forty years ago the interamerican highway was full of holes and had even more curves than it does today. It took Ricardo and me four hours to drive from San José to San Isidro de el General. Pulling into town we filled the Land Rover with diesel at the Gasotica, one of two service stations in town. The other was the Texaco which was located where today there is a Pizza Hut. The highway was paved, but all the streets in San Isidro were gravel. After buying some supplies at the central market, where today stands the cultural center, we drove through town and asked a man on horseback for directions to Dominical. He pointed us down the street that ran along the west side of the park. It took us past the airport, which stretched from where today we find the new central market, south past the soccer field, and all the way to the bar called “Uno Mas.“ Soon we were on the outskirts of town stirring up dust on a bumpy gravel road which eventually took us up some extremely steep hills and straight over the top of El Alto de San Juan. Even though the road was dry we wouldn’t have made it up that hill without 4WD. Two and a half hours from San Isidro, after passing through four small villages and fording four streams, we arrived at our destination, a place called Hacienda Baru. That was my first view of la casona hidden behind a grove of mango trees 100 meters from the road.

The house was obviously new. Though unpainted the wood had the natural color and brightness of recently milled lumber rather than the gray, dried look characteristic of older wood. The design reminded me of the banana company villages with the kitchen and open porch downstairs, and four bedrooms upstairs, one in each corner. There was an old, blue, Ford tractor parked on the first floor, taking up about a third of the porch area. Ricardo parked the Land Rover next to the tractor. We stepped out and stretched our weary limbs after nearly seven hours of travel in the rough riding vehicle. The month was February, and the year 1972.

The foreman, Daniel Valverde, one of three workers, walked up and introduced himself. He offered to show us the house. The kitchen, located directly in front of where we were parked, was long and narrow. There was a large concrete sink and a shower behind the kitchen, as well as a real oddity for these parts, a flush toilet. Most homes had only an out-house. Unfortunately we had no running water, so the toilet wasn’t much use to us. Daniel explained that the free flowing spring always dried up in late January. We would have to go to the Barú River to bathe, and we were both wondering about other corporeal necessities. Fortunately the weeds were high in the pasture behind the house. There was no furniture of any kind. We knew this would be the case and had come prepared. From the back end of the Land Rover we unloaded a couple of mattresses, folding chairs, a camp stove, some bare basic cooking and eating utensils, and a bag of candles.

We were standing under an almond tree with Daniel and his wife when several chickens walked by. “How much for that young rooster?” asked Ricardo, looking at Daniel’s wife.

“Two colones,” she replied, her eyes on the ground.

“If you’ll cook him for us it’s a deal.”

“Two fifty cooked,” came the answer in a low voice, still looking at the ground.

“You’ve got your self a deal.” Ricardo bent down, pulled a pistol out of his boot, and shot the rooster dead on the spot. “There. You don’t even have to kill him,” he laughed and put the pistol back in his boot. My lower jaw dropped several inches. Daniel and his wife didn’t appear to be the least bit surprised.

It was late afternoon and we were tired and hot. “I can hear the waves, but I can’t see the beach.” I looked at Daniel. He explained how to get there, and away we went. When we returned a couple of hours later it was dark out, and our chicken dinner was ready.

The Big Move

During the next four years I split my time between Hacienda Barú, a big ranch on the Caribbean side of the country, and my family in San Jose. In 1976 I went into partnership with the owners of the hacienda, and began working there full time, spending only weekends in San Jose. A couple of years later in 1978, the whole family moved from the big city to Hacienda Barú, my wife Diane, our 13-year-old daughter Natalie and Chris, our son of seven years. It was the beginning of an enormous adventure. Though we didn’t know it at the time, Diane and I would live in la casona for the next 16 years.

We weren’t exactly city slickers. Both of us had grown up in rural environments in the United States, but she and the kids had been living in San Jose for the last 8 years, and were used to certain creature comforts that weren’t forthcoming at la casona. I’m talking about things like electricity, telephones, TV, super markets, doctors, and English speaking neighbors. The adaptation process was tough for everyone, especially Diane.

We made a few changes to la casona itself, the most important of which was closing in the downstairs and erecting a separate roofed area to park the car and tractor. At first our outside walls were nothing more than wire mesh, but this was eventually replaced with wood. The wire mesh didn’t provide much privacy, but it kept all of the domestic animals out. Our menagerie included everything from guinea hens to goats, a pig that Chris won in a raffle, and of course cows. She wasn’t exactly domestic, and the wire mesh didn’t stop her from coming into the house, but we had a friendly snake named Agatha who lived in the attic and ate bats.

Schooling

Seven-year-old Chris entered the first grade at Barú, five kilometers from la casona. He shared a classroom with 27 students from six grades all taught by the same teacher. Class began at 7:00 AM and everyone went home at 11:00. Sometimes he rode his horse, and occasionally we took him and some of the neighbor kids in the car. The Dominical school was closer, as the crow flies, but there was no bridge over the Barú River. Chris loved every minute of his schooling at Barú. The part he hated was the home study in English in the afternoon. There were much more interesting things going on outside, like riding horses, working with cattle, talking with the workers, and fishing. He graduated from the Barú elementary school in 1984 and began two years of junior high school by correspondence. That was definitely tougher on Diane and meI than on Chris. In the end it all worked out fine. He eventually graduated from the eighth grade with an accredited correspondence school, and went to the US to live with family and attend High School. Diane says that boys are adventurers and girls are nest builders. To Chris, who grew up in the jungle, going to the states and living in a city was a big adventure. He thrived in his new environment and never returned to Costa Rica to live. Today he is an architect, is married, has two kids, and lives in Boulder, Colorado.

Natalie had completed elementary school at the Country Day School in San Jose. When we moved to Hacienda Barú she entered the Colegio at Matapalo. Surprisingly she adapted rapidly and loved her new environment. She rode an old yellow school bus the kids called the “tin can.” Among other defects, it lacked brakes, and no repair parts were available. Other than that it was in pretty good shape, considering its age. The driver would honk the horn a couple hundred meters from the house, so Natalie could dash from the house to the road. The driver slowed down as much as possible while she ran beside the bus and leaped up onto the first step, a simple task for a healthy young teenager. Getting off the bus, basically the reverse, was also no problem, but occasionally provoked a fall and a skinned knee.

Convincing Natalie to leave her new school and friends and go the US for high school was a major battle. We didn’t exactly have to hog-tie her and carry her to the plane, but neither did she go willingly. Nevertheless, she did well in high school, graduated in four years, and couldn’t wait to get back to Costa Rica. Upon her return she started taking university courses in San Jose, and working in a travel agency. Today she has worked with the same company for nearly 30 years, and lives in San Jose with her two children.

Family Life

Surrounded by a multitude of modern gadgetry and mediums of entertainment, today’s youth has a hard time imagining how kids could possibly deal with the boredom of living without electricity, computers, video games, and telephones. The truth is that boredom just wasn’t part of our lives. In fact some of my happiest memories are of life in la casona, and I think the rest of the family would agree.

The days were filled with work, and there never seemed to be enough time to get it all done. A multitude of activities filled our evenings. We listened to Voice of America, BBC, and variety of other stations from around the world on the short wave radio. We read a lot by kerosene lantern, and we all became accomplished backgammon players. Cribbage was also popular. My favorite evening entertainment was our monthly cock roach hunt. The roaches loved the dim lighting provided by kerosene lamps. Our weapon was a special fly swatter that consisted of a spring-loaded plastic pistol that shot a plastic disk about two meters, and, hopefully, smashed the prey. A roll of the dice determined who got to go first. The player had one minute to find, stalk, and kill a cock roach with one shot. Success resulted in the right to another shot. Failure ended the turn, and the pistol passed on to the next shooter. The first time the pistol made the full round of all the players, and nobody killed a roach, the game was over. The shooter with the greatest number of kills was the winner. A good hunt ended with upwards of 100 kills. It took about a month for the cock roach population to reestablish itself.

Our weekly shopping trips to San Isidro always began on Thursday. Leaving before noon to avoid the rains put us in San Isidro at mid afternoon. We checked into the newest hotel in town, the Amaneli, and did a little shopping. On Friday morning it was up early and off to the farmer’s market to get first pick of the produce. After breakfast we finished the shopping, checked out of the hotel, and headed for the ice factory. Due to the limited capacity of our butane refrigerator we acquired a large ice chest that would hold an entire block of ice and several kilos of meat. Lunch at Bahía Restaurant was followed by the bakery, the butcher shop, and off to Hacienda Baru before the afternoon rains.

The lack of telephones spurred us to look into amateur radio as an alternate means of communication. Radios could be operated with batteries, and we could charge a 12 volt battery in the car or the tractor during the day, and use it to operate the radio at night. Diane, Chris, and I studied, took the exams, and acquired our ham radio licenses. My call sign was TI 8 JEE, which over the radio was often pronounced phonetically as “Tango India 8 Juliet Echo Echo.” At first we only communicated within Costa Rica, but as our enthusiasm grew we moved on to more and more sophisticated radios and antennas, and were eventually talking with people from all over the world. Just before lunch we met with a group of hams from Panama, in the evening with the New Zealand and Australia crowd, and on really good nights with Antartica. We were totally captivated by the amazing world of amateur radio. I remember that all of the Panamanians went off the air, took down their antennas, and hid their equipment during Manuel Noriega’s reign, lest they be accused of revolutionary activities. A few came back on air the day the US invaded Panama, and the rest a few days later when Noriega was arrested. During hurricane Joan our radio was a life line between the community of Dominical and the Comisión Nacional Emergencias. I was out of the country at the time, and the CNE put Diane in charge of the local emergency committee. Six days after the initial torrential rains, road conditions permitted my return to home. Dominical had been isolated for the last five days. Diane was thin and tired but filled with the satisfaction of knowing she had made a difference. Medical emergencies were dealt with, lives were saved, and delivery of food and medical aid was coordinated by way of Diane’s radio and our Chevrolet Blazer. The call sign TI 8 DEE was long remembered in the CNE.

The arrival of electricity in our area in 1986 was the beginning of a learning experience, or rather a relearning experience. We no longer had to trim the lantern wicks and get out the candle holders every afternoon at dusk. Nearly every weekly shopping trip brought a new electrical appliance to our home. First was the fridge, followed by the washing machine, blender, and toaster. It was with a twinge of sadness that we retired our old hand-cranked coffee grinder and the white cloth bags for straining coffee. It was like losing a treasured part of past years, a clear reminder that times were changing and would never again be the same.

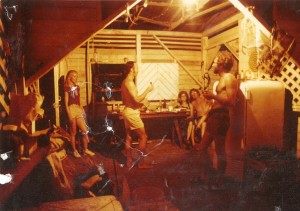

In 1994 Diane and I built our present home in another part of Hacienda Barú and moved away from la casona. Cattle ranching was now part of our past, and Hacienda Barú was moving full force into ecological tourism. La casona became home to guides, interns, and volunteers. A woman from Hatillo, named Doña Leticia, came there to live with her two kids, became the lady of the house, and cooked and cleaned for the occupants. La casona was demolished in 2011. In its place stands the Hacienda Barú Biological Research Center. I know that the new center will grow to be an important source of biological information and a great stimulus to research and conservation in the Path of the Tapir Biological Corridor, but I will always remember with great fondness those 16 years of life in la casona.

Author’s note: When I began writing this article I soon realized that squeezing all of the memories into one short essay wasn’t going to be possible. To fit this small sample of life in la casona into one article, I had to do some serious condensing. In fact each paragraph could easily be expanded into one or two chapters of a book. Maybe someday soon, things will change in my life and I will finally be able to retire and write it.