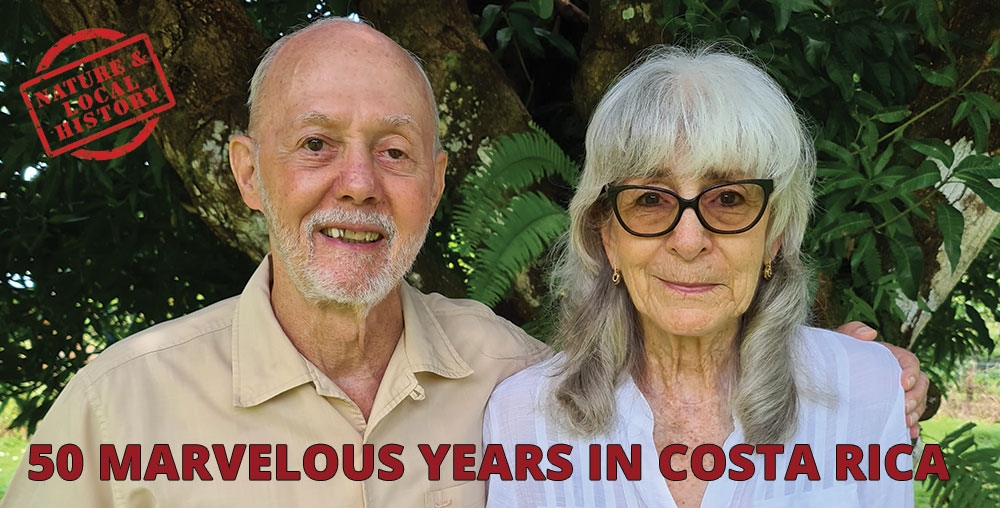

50 MARVELOUS YEARS IN COSTA RICA

On December 13, 1970 when my wife Diane, our 4-year-old daughter Natalie, and I, accompanied on our flight by 37 head of cattle, arrived at El Coco International Airport (SJO) on a DC 6 four-engine propeller plane, we thought that we would be staying for four months, the duration of

Read More